After spending a semester studying the history, culture and politics of chocolate at Harvard University with Professor Carla D. Martin, I decided to host a chocolate tasting to put to test what had been presented in class and in our readings. My invitation to the tasting was enthusiastically accepted by several friends who love, of course, all things chocolate. My goal was threefold: to educate them about the anatomy of a chocolate bar, to explore some of the issues facing the chocolate industry today, and to examine the packaging and significance of certifications. By increasing their awareness of these topics, I hoped to inspire them to become more conscientious consumers.

THE TASTING

The challenge quickly became which chocolate bars to include in my taste test. Walking down the aisles of a few local grocery and convenience stores proved daunting. There were just so many bars to choose from. In The New Taste of Chocolate, Maricel E. Presilla writes, “the face of chocolate has changed fantastically in the last few years in that shoppers now find themselves confronted with some bewildering choices” (p 126). And bewildered I was. When surveying the multitude of labels, I considered ingredients, certifications, and messaging. Ultimately, I arrived at a sample of seventeen bars including three different milk chocolates, a few dark chocolates with varying amounts of cocoa, and a selection of bars with additional ingredients such as almonds, mint, caramels, and sugar substitutes. I also included one raw cacao bar to see how it would fare. In addition, I selected several bars that had specific certifications and messaging on their packaging to prompt discussion about the issues in the chocolate industry today.

I elected to host a blind taste test so that my friends could judge each chocolate free from pre-conceived notions, preferences, and packaging information. I assigned each bar a letter and created a spreadsheet which the participants used to record their results. I instructed them to use all of their senses to fully experience each chocolate bar. First, they looked at each sample for color and sheen. They then smelled the chocolate to enjoy the aroma. After breaking each sample to experience the “snap”, they tasted them. My group proved to be very enthusiastic and shared their findings with great description using terms such as “sweet,” “too sweet,” “artificial,” “chalky,” “salty,” “milky,” “creamy,” “delicious,” “nutty,” “fruity,” “bleh” and “awful.”

The general consensus among this group was that they preferred dark chocolate to milk, and favored a bar with a cocoa content of around 70%, finding a bar with 85% cocoa too bitter. As a group of mostly affluent, educated and health conscious women, they liked bars with natural and organic ingredients rather than artificial flavors and soy lecithin. In her article “Fresh off The Farm”, Patricia Unterman explains, “when you choose to eat organic and sustainably raised produce, a little karma rubs off on you and makes everything taste better,” which resonated with this group. I found it interesting that they all readily identified the Hershey’s milk chocolate bar and agreed it reminded them of their childhoods. Though they admitted they don’t regularly consume Hershey’s, they still enjoy it as a key ingredient in s’mores. Most of them enjoyed chocolate bars with nuts, few liked fruit additives, and only one liked the raw bar. Some were pleasantly surprised by the bars with the artificial sweetener Stevia. They considered them to be “less guilty” treats having no sugar and fewer calories.

BEYOND THE BAR

I concluded the tasting with an analysis of the packaging of the different bars. We looked at the manufacturer, their messaging, list of ingredients, bean origination and certifications. While some of the participants were familiar with the various certifications, most were not and only one was familiar with the issues present in the chocolate industry today. The group expressed a desire to gain a broader understanding of these issues so that they could be more discriminating in their choices and use their purchasing power to support the causes they felt most strongly about. In Eating Out: Social Differentiation, Consumption and Pleasure, Warde and Martens note “consumption practices are driven by a conscious reflexivity such that people monitor, reflect upon and adapt their personal conduct in light of its perceived consequences.”

The industry today is fraught with many interrelated challenges including the worst forms of child labor, poverty, and sustainability to name a few, and certifications allow consumers to learn which chocolate companies support ethical and sustainable practices. Worst forms of child labor include slavery, trafficking, debt bondage and any work by its nature that is harmful to the health, safety and morals of children (Martin, April 21). In The Fair Trade Scandal: Marketing Poverty To Benefit The Rich , Ndogo Sylla explains child labor is extensively utilized in cacao harvesting and estimates that 2 million children work in the West African countries of Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana. Cacao farmers labor under difficult circumstances and are subject to physical injury and exposure to toxic pesticides while earning on average $.50 to $.80 per day per capita making it virtually impossible to support a paid labor force or sustainable farming practices (Warde and Martens, p 497).

CERTIFICATIONS

The idea of fair trade dates back to the late 1940’s and has evolved over the past 70 years with the goal to reduce poverty through everyday shopping. A multitude of organizations strive to tackle poverty in the poorest countries by improving workers’ social, economic and environmental conditions. Others raise awareness and work to protect endangered species and the planet. The images and links below represent some of the different certifications we discussed:

:

:

Fairtrade International(FI) is a multi-stakeholder, non-profit organization focusing on the empowerment of producers and workers in developing countries through trade. Fairtrade International provides leadership, tools and services needed to connect producers and consumers, promote fairer trading conditions and work towards sustainable livelihoods. https://www.flocert.net/glossary/fairtrade-international-fairtrade-labelling-organizations-international-e-v/

Fair Trade Certified enables sustainable development and community empowerment by cultivating a more equitable global trade model that benefits farmers, workers, fishermen, consumers, industry, and the earth. We achieve our mission by certifying and promoting Fair Trade products. https://www.fairtradecertified.org

Equal Exchange Equal Exchange’s mission is to build long-term trade partnerships that are economically just and environmentally sound, to foster mutually beneficial relationships between farmers and consumers and to demonstrate, through our success, the contribution of worker co-operatives and Fair Trade to a more equitable, democratic and sustainable world. http://equalexchange.coop/about

UTZ Certified shows UTZ stands for sustainable farming and better opportunities for farmers, their families and our planet. The UTZ program enables farmers to learn better farming methods, improve working conditions and take better care of their children and the environment.Through the UTZ program farmers grow better crops, generate more income and create better opportunities while safeguarding the environment and securing the earth’s natural resources. Now and in the future, consumers that products have been sourced, from farm to shop shelf, in a sustainable manner. To become certified, all UTZ suppliers have to follow our Code of Conduct, which offers expert guidance on better farming methods, working conditions and care for nature. https://utz.org

Rainforest Alliance Our green frog certification seal indicates that a farm, forest, or tourism enterprise has been audited to meet standards that require environmental, social, and economic sustainability. It is a non-governmental organization (NGO) working to conserve biodiversity and ensure sustainable livelihoods by transforming land- use practices, business practices and consumer behavior. https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/faqs/what-does-rainforest-alliance-certified-mean

AND THE WINNER IS

After much deliberation, considering aroma, color, sheen, snap, flavor and texture, the group unanimously agreed the Hachez Cocoa D’Arriba 77% Classic was their favorite. One taster exclaimed, “It’s so creamy and the flavor is so rich.”

THE HACHEZ STORY

Joseph Emile Hachez, a chocolatier of Belgian origin, established The Bremer HACHEZ Chocolade GmbH & Co. KG in 1890 in Bremen, Germany. Though the company has changed hands several times over the past century, Hachez remains one of the most well-regarded producers of superior chocolates in Germany. As highlighted on their packaging, “Hachez offers authentic chocolates of superior quality and craftsmanship-from the cocoa bean to the chocolate bar.”

“Still using the original recipes, they are one of the few German chocolate manufacturers to do everything in one location – from cleaning the cocoa beans to roasting them, molding the chocolate and packaging them. This allows them to oversee each stage of manufacturing to ensure every last piece of chocolate meets their high standards” (Chocoversum.de).

About 100 hours of work are put into every cocoa bean which leaves the factory in Bremen as chocolate. The CHOCOVERSUM shows the tradition and the attention to detail, which is practiced in the HACHEZ chocolate factory in Bremen by over 350 employees on a daily basis. (Chocoversum.de)

Though their packaging displays no certifications or social, political or environmental messaging, Hachez belongs to both BDSI, the Association of German Confectionary, and GISCO, the German Institute on Sustainable Cocoa, which aim to address some of the issues facing the cacao industry today. The BDSI works to improve the standard of living for cocoa farmers and their families by promoting sustainable farming and education, and by offering loans to farmers to fund investments to increase productivity, quality and efficiency. They find exploitive child labor practices unacceptable and are working with local communities to eliminate it through education and schooling. BDSI intends to boost the percent of sustainable cocoa in manufacturing to 50% by 2020 and to 70% by 2025 and to increase the share of responsibly produced cocoa in chocolate and confections sold in Germany. Similarly, GISCO’s focus is to improve the living conditions of cocoa farmers and their families and to conserve natural resources and biodiversity in cocoa producing countries.

THE ANATOMY OF A HACHEZ BAR

To understand the anatomy of any chocolate bar, it is essential to consider all of the ingredients and workers that contribute to the final product. The basis for chocolate is cacao, which is derived from the seed of the tree, Theobroma cacao, or “food-of-the-gods cacao.” These trees grow in a band around the world, hugging the equator, and thriving only where there are perfect temperatures and plentiful moisture (Off, p 10). Approximately 70% of the worlds cocoa comes from West African, in particular, Cote D’Ivoire and Ghana. Latin America accounts for 16% of cocoa production and Asia and Oceana account for another 12%. Over 10% of the global harvest is processed in Germany where Hachez is based.

Farmers gently separate the cacao pods from the trees and crack them open to remove the pulp which encases the precious beans. Once cleaned of debris, the beans and surrounding pulp are covered in banana leaves to begin the important process of fermentation which develops the flavor of the beans. The fermentation process can take between two and six days. When fermentation is complete, the beans are dried, sorted and bagged for shipment.

At Hachez, they claim to use only the finest cocoa varieties from farmers whom they consider to be socially responsible, environmentally friendly and practice sustainable farming. The unique flavor characteristics of the variety of beans they use reflect their terroir, “loosely translated as ‘a sense of place,’ which is embodied in certain characteristic qualities, the sum of the effects that the local environment and people have had on the production of the product” (Martin, April 18).

Upon receiving the beans, Hachez’s chocolatiers sort them and run them through a machine to remove stones, sticks, and other foreign substances. Next, the beans are “roasted in traditional drums using hot air currents to extract the optimal development of flavor and aroma” (Chocoverse.de). After a winnower separates the husks from the nibs, Hachez grinds the nibs specifically to a granular diameter of .0014 mm to produce a more delicate texture. Next, the chocolate is put through a conche for up to 72 hours to reduce the size of the particles in order to fully refine the aroma and to enhance the smoothness and delicate consistency. The chocolate is then tempered: “the temperature of the mass is raised, then carefully lowered so that the crystal structure of the fat may be destroyed to prevent the bar from becoming blotchy and granular, with a poor color. Tempering remains a vital step in the manufacture of the finest quality chocolate” (Coe and Coe, p 248). The end result is a chocolate bar with great aroma, sheen, snap, flavor and texture. As one taster exclaimed, “This bar is amazing. The rich flavor and creamy texture make it the best one by far.”

CONCLUSION

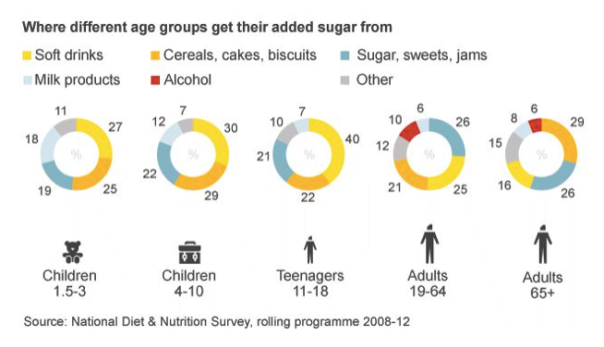

Near the end of the tasting, we explored the health benefits of chocolate when consumed responsibly. Chocolate with the greatest health benefits has a minimum 70% cacao, is organic, has limited amounts of cocoa butter and added fats, and is enjoyed in small amounts of about 2 oz. per day (Martin, April 11). Scientists have identified in cacao antioxidant properties which reduce disease causing free radicals. Antioxidants like this help ward off cancer, repair damaged cells, and impact the effects of aging. Dark chocolate in particular is high in polyphenols and flavonoids providing a large dose of antioxidants per serving. Flavanols, the main type of flavonoid found in dark chocolate, also are known to positively affect heart health because they help lower blood pressure and improve blood flow.

The tasters left feeling much smarter about the bean to bar process, more aware of the issues facing the chocolate industry today, enlightened about the health benefits of dark chocolate, and most important, empowered as shoppers. I would argue I succeeded in turning them into conscientious consumers.

Works Cited

Coe, Sphie D. and Michael D. Coe, The True History of Chocolate. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2006 (3rd Edition).

Mintz, Sydney W., Sweetness and Power. London: Penguin Books Ltd., 1985.

Off, Carol, Bitter Chocolate, Anatomy of an Industry. New York: The New Press, 2014.

Martin, Carla D. “Modern Day Slavery”, Harvard University, AAS E119, March 21, 2018.

Martin, Carla D. “Health, Nutrition, and Politics of Food”, Harvard University, AAS E119, April 11, 2018.

Martin, Carla D. “Psychology, Terroir and Taste”, Harvard University, AAS E119, April 18, 2018.

Presilla, Maricel E., The New Taste of Chocolate Revised. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2001.

Unterman, Patricia, “Fresh off the Farm”, SF Examiner, Aug 20, 2000.

Warde, A. and I. Martens, Eating Out: Social Differentiation, Consumption and Pleasure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Sylla, Ndongo Samba. The Fair Trade Scandal: Marketing Poverty To Benefit The Rich. 1st ed. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University, 2014.

Chocoversum by Hachez. https://www.chocoversum.de/en/

Association of the German Confectionary Industry. https://www.bdsi.de

German Initiative on Sustainable Cocoa. https://www.kakaoforum.de/en/

You must be logged in to post a comment.