In a developed world such as ours, the enjoyment of luxury living often comes with a price – both figuratively and literally. The literal monetary price of certain common items is based on the cost of production – lower the overhead cost; more the consumer can save on spending. The figurative moral cost of these goods is based on the extreme conditions and measures taken to cut production cost. Often in developed worlds, there is ignorance – willful or genuine – between the products we buy and the production process the items had undergone. The products range from electronics such as smartphones to food stuff like chocolate. As different as these products are, they share the same production measures used in order to become marketable to consumers in the developed worlds. The main focus of the cost-cutting in production supply chain is the cut to labor cost; specifically the lowest wage one can pay one’s employees for the production of goods in order to flood the market with the products. This practice of labor cost-cutting is not new at the local level, but globally, the origin and impact of this practice can be traced back to the Atlantic Slave Trade that started in the 15th century in the New World of the Americas. In the following assessment, I’ll talk about the past history of slave trade and globalization of trades and the modern slave trade and its impact.

Globalization and Historical Slavery

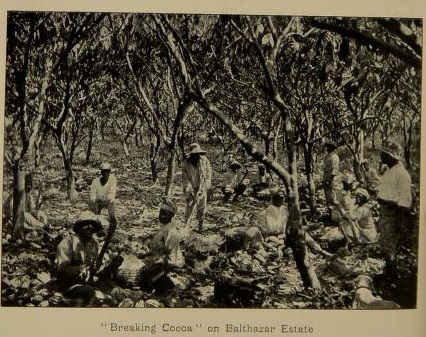

Long before “Made in China” became a hot contested topic during U.S. Presidential campaigns, the need for cheap labor to maximize corporate profit was in the minds of settlers and first-generation corporations – joint-stocks – such as the West India Company and the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company respectively for trades in the Americas and Southeast Asia. The plantation system setup by the mass production of sugar, also known as Brown Gold, in the Caribbean sets the stage for the use of a massive slave labor force. The two main reasons for this were the decline in European indentured workers due to the tough sugar labor practices and the plantation owners’ thought that Africans were better suited for the tropical climate (Higman p. 120-125.) According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, there were a total of over 12.5 million slaves traded from West Africa (see Figure 1 below.) The more profitable practice of using free African slave labor instead of indentured European workers continued until the former’s abolition and upon which saw a massive inflow of indentured workers from India who continued on and saved the sugar and cocoa industry (see Figure 2 below) in the 19th century (Higman p. 218-220.) As religious as most Europeans were in the past, certain groups had stood up and fought against the immoral and unethical practice of slavery. A curious case in history: in 1596, a captured Portuguese ship turned up in the Netherlands (Middleburg, Zeeland province) with 130 African slaves, and when the townspeople rejected the practice of slave trade, the slaves were set free. During that time, the Spanish and the Portuguese (Catholics) were enemies of the Dutch Protestant Republic of the Seven United Provinces. However, after the Dutch established sugar product in Brazil, a large workforce was needed so went the moral high ground (Emmer p. 13-14.)

According to a New York Times’ reporting, in 2012, then-President of the U.S. Obama had a meeting with leaders of the IT Industry where he asked Apple’s Steve Jobs about the possibility or probability of making the popular iPhone in the U.S., to which according to an attendee Jobs answered improbable. The NYT’s report continued to state that in 2011, Apple earned more than Goldman Sachs, Exxon Mobil, or Google, at over $400,000 per employee. Such profit margin is made possible by a large, cheap Chinese labor force. For cocoa production, a similar practice can be found. According to an analysis done by the non-profit organization, Food Empowerment Project (FEP), child slavery for cocoa production in West African states is a big issue, specifically Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana. According to the FEP research, the main cause of child slavery and trafficking in the West African countries was extreme poverty. In the U.S. State Department’s 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report, the trafficking expanded to include children from Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali, and Togo, who were found in Cote d’Ivoire (DoS p. 142-144.) The question one might ask, then, does the $1 USD candy bar worth the pain and suffering of children in another continent? In an interesting 2006 conscientious consumption study done by a group of scholars, a choice between ethical and unethical products was given to a group of people in Detroit area of around 40,000 people. The subjects were given a choice between common cheap socks and “ethically” produced – sweatshop free – socks but with a premium added to its final price. The initial response from the subjects was not exactly in tune with their final decisions, where only some would pay the higher premium. However, the study did highlight the need for consumers’ education in identifying and knowing the origin of the product that they purchase.

Conclusion:

Comparing the moral high ground taken by the Dutch in the late 1500s and their eventual caved-in to the production demand to the conscientious consumer study of 2006, I discovered that organizations, or simply a group of people, will hold a moral high ground as long as it’s convenient to do so. However, I also noticed the impact of demand and its effect on the production practices. Growing up in Hong Kong and Macau in the 1980s, I often find myself hanging around my mum at her place of work – a clothing factory. Like most poor families at the time, I was presented with an opportunity to work off-the-books doing tasks such as trimming the loose string from the sewed labels on t-shirts, jeans, etc. Like many children living in poverty, I never thought of it as child labor at the time. Is it truly possible for a consumer society to demand corporations to be more responsible, especially when the consumers, directly (stocks) or indirectly (pensions or mutual funds), are investors in those companies? Before I end my assessment, I’d like to leave the readers with an artwork done by Benjamin Harris in 2016 titled “You Are Eating My Flesh.”

References Cited:

Harris, B. You Are Eating My Flesh. 20 August 2016. Walsall Old Square, U.K. http://benjaminharrismusings.blogspot.com/2016/08/you-are-eating-my-flesh-2016-chocolate.html Accessed 09 March 2017.

Duhigg, C. & Bradsher, K. “How the U.S. Lost Out on iPhone Work.” The New York Times, 21 January 2012, Business Day-The IEconomy. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/business/apple-america-and-a-squeezed-middle-class.html

Food Empowerment Project. Child Labor and Slavery in the Chocolate Industry. 2017. Accessed 09 March 2017. Retrieved from http://www.foodispower.org/slavery-chocolate/

U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report June 2016. U.S. Government. June 2016. Accessed 09 March 2017. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf

Prasad, M., Kimeldorf, H., Meyer, R., & Robinson, I. (2006). Consumers With A Conscience: Will They Pay More? Contexts, 5, 24-29. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/documents/2013/may/consumer_conscience_study_ME_20130501.pdf

Vaquero. Life and Adventure in the West Indies: A Sequel to Adventures in Search of a Living in Spanish-America. London: John Bale, Sons & Danielson, 1914.

Higman, B.W. A Concise History of the Caribbean. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Emmer, P.C. The Dutch Slave Trade: 1500-1850. New York: Berghahn, 2006.

Estimates Database. 2009. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. http://www.slavevoyages.org/estimates/qwQasWCo accessed 8 March 2017.