Cacao and the tools used to cultivate and process it have changed tremendously since its original discovery to now. From being a food that was only consumed by the elite to a food enjoyed by billions worldwide. However, the original form of cacao and the way it was consumed is very different to how it’s consumed now. One of the few things that has remained consistent are some of the traditions carried when consuming cacao, one of them being consuming it as a beverage. A specific tool, the molinillo, has withstood the test of time and continued to be used in households to create the delicious beverage most of us love and consume regularly.

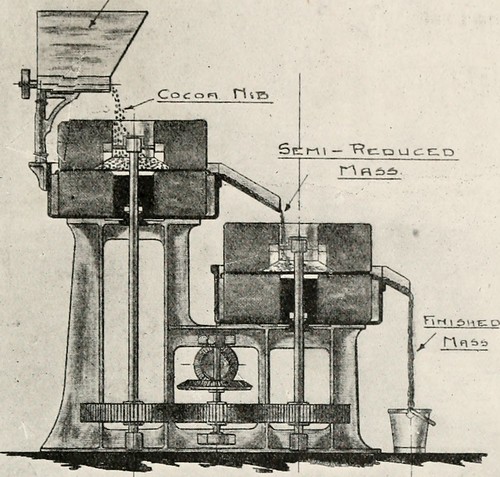

Cacao was extremely important to Mesoamerican civilizations as early as 1500 in the Olmec civilization. As centuries passed, the processing and consumption of cacao became more complex, as pre-Columbian Mayan books written in hieroglyphics feature cacao throughout them as being food of the gods, only for the elite to consume. In the Mayan Civilization, cacao had many purposes, such as for flavoring food or medicinal uses. However, its most common form was as a beverage, which was thought to have healing properties and be attributed to the gods. Over time, the Aztecs crafted their own chocolate beverage recipe, which included grinding roasted beans and other spices on a metate, a ground stone tool, forming a thick paste which was combined with hot water and poured from pot to pot as to not separate (Lane). This method of pouring from cup to cup as highlighted in the Aztec Codex Tudela as a woman aerating the beverage was how the Aztecs originally created foam in the chocolate beverage and avoided separation. When the Spanish arrived in Mesoamerican in the 1500s, they were fascinated with the drink and were determined to simplify the process of creating this delicious beverage, and thus, the molinillo was created (Lane).

What is now a common household staple in many Latin American kitchens, the molinillo is a unique and prized apparatus that dates back centuries and carries with it the rich culture and history of the importance of chocolate, specifically chocolate beverages in Latin American and European households (Edwards). The modern molinillo is approximately 11.5 inches long, hand carved and painted wooden stick with a knob on one end and slender handle at the other (Edwards). The gadget has been used for centuries to froth up chocolate beverages by creating a foam when rolled between the hands. According to ancient tradition, the foam that is created “embodies the spiritual essence of the chocolate” (Edwards). However, the original molinillo, created by the Spanish, was much smaller and less intricate than what is typically seen today.

Instead of having to pour the paste with water from pot to pot, the Spanish invented a small wooden stick with a sphere at the end to stir the paste in one container and avoid separation (Bowman). This creation, which was started in Mexico, was shared with the Natives of Mesoamerican, and with that idea they created larger, more intricate versions of the molinillo. There is even a drawing of a Native Mesoamerican man holding the early molinillo with a chocolate pot at his feet, indicating that the molinillo was easily adapted by the Natives. Over time, this simple wooden stick eventually developed into the modern molinillo that we see today, which many households use to retain the tradition of chocolate beverage-making.

While the use of the tool has not changed much over time, the preparation of the beverage has, and its simplicity yet adaptability is what makes the molinillo so unique and important as it carries the history of the beverage. The tool that was first invented by the Spanish and adopted by the Mesoamerican Natives was used to stir a bitter beverage that had spices such as achiote, and it was this beverage that was originally coined “food of the gods” and was drank by the elite, particularly for ceremonial purposes (Lane).

When the Spanish conquistadors brought the drink and recipe back to Europe in the mid 1500s, it caused a revolution and became the King’s Official Drink in Spain (GourmetSleuth). The drink was only consumed by the royal and elite. However, unlike Mesoamericans, Europeans had already been introduced to sugar since the mid 1100s (Edwards). Europeans mixed sugar into the recipe and replaced the bitter achiote spice with a sweeter cinnamon spice (Bowman). This drink became a phenomena and eventually became what we know today as hot chocolate. Throughout this time, the molinillo has prevailed as a testament to an item that withstands a changing recipe. While the molinillo was first used to ensure the chocolate beverage did not separate, emulsifiers in modern chocolate beverages ensure the beverage stays mixed (Bowman). However, the molinillo is used in households to froth the beverage and continue to create that spirit and essence in the original food of the gods.

Images Cited

https://chocolateclass.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/75722-mujer_vertiendo_chocolate_-_codex_tudela.jpg

https://www.staugustine.com/article/20091228/NEWS/312289984

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16035/16035-h/images/g041.jpg

https://www.gourmetsleuth.com/articles/detail/molinillo

Works Cited

Edwards, Owen. “A Historic Kitchen Utensil Captures What It Takes to Make Hot Chocolate From Scratch.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Sept. 2007, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/kitchen-utensil-chocolate-stirring-from-scratch-cacao-161383020/.

Bowman, Barbara. “Molinillo – Mexican Chocolate Whisk (Stirrer).” Gourmet Sleuth, Published by: Gourmet Sleuth, http://www.gourmetsleuth.com/articles/detail/molinillo.

Lane, Marcia. “A Sweet Discovery.” The St. Augustine Record, The St. Augustine Record, 28 Dec. 2009, http://www.staugustine.com/article/20091228/NEWS/312289984.

“Molinillo or Chocolate Whisk.” National Museum of American History, americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1460190.

Figure 1: A close up of the glyph that helped identify this vessel. This symbol meant “cacao” in the Classic Maya period.

Figure 1: A close up of the glyph that helped identify this vessel. This symbol meant “cacao” in the Classic Maya period.

You must be logged in to post a comment.