Chocolate’s Evolution

Walking into an average American supermarket, one would be able to find chocolate in several different aisles of the store. There may be chocolate croissants in the pastry section, solid chocolate bars in the candy area, and chocolate milk in the drink aisle. Cacao now takes on a multitude of forms and is widely accessible by people from across the globe and across socioeconomic classes. However, cacao used to only be affordable for elite circles and royalty and was simply served as a chocolate beverage.

Chocolate popularity has been able to spread from elite Europeans to broader audiences across social classes due to the changing form of chocolate. Cacao has been consumed in a variety of ways, ranging from as a liquid to as powder to as a solid block, and tracing the evolution of how the cacao bean has been used and taken shape over time can help illuminate how the ingredient has transcended socioeconomic divides.

Liquid Form

Cacao had its origin in Mesoamerica as a fine crafted drink; the beverage was mostly enjoyed by the nobility during the times of Olmec, Mayan, and Aztec civilizations. The liquid form of cacao was believed to have been consumed by the gods and thus was a sacred product in every aspect of elite Mayan culture. The drink was manually processed and typically flavored with ingredients native to the region, such as vanilla and achiote (Coe and Coe 61). The Mayan served cacao beverages at feasts as a display of wealth and power and even incorporated it into negotiations and political pacts (Leissle 30). Similarly, this elite drink was reserved solely for the nobility in the hierarchical Aztec society but served cold rather than hot (Coe and Coe 84). Cacao beans, consumed solely as a beverage among the Aztecs, were ground into a powder, mixed with water, and then poured from one vessel into another to obtain the sought after foamy texture (Coe and Coe 98).

By 1519, European colonizers such as Hernán Cortés were introduced to cacao and exploited its potential for consumption by introducing it to Spanish royalty. Although the Spanish incorporated different spices such as sugar and cinnamon into the drink, the chocolate beverage remained a sign of luxury that only those with wealth and power could afford (Klein). The popular beverage soon spread to the elite families in France and England and in 1657, the first chocolate house opened in England. These houses provided the English elites with a place to discuss the most controversial political issues of the day and socialize over a cup of hot chocolate. To further establish the drink as exclusive to the upper class, the Europeans drank their chocolate from ornate dishes made from precious materials that are comparable to the embellished ceramic vessels that the Mayan and Aztec rulers had utilized.

(From 1717 to 1720)

Powder Form

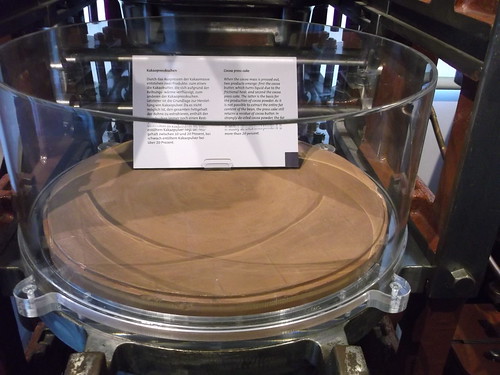

By the 18th century, chocolate was widely regarded as a luxurious good and it wasn’t until the early 19th century with the onset of the Industrial Revolution that it became accessible to the lower classes. In 1828, a Dutch chemist invented a cocoa press that revolutionized the way that Europe was able to produce and consume chocolate. The Van Houten press squeezed out the cocoa butter from roasted cacao beans, leaving behind a dry compact cake that could be pulverized into a fine powder that became known as “Dutch cocoa” (Coe and Coe 234). Such a separation allowed for the individual sale of cocoa powder on a mass scale and an improvement in chocolate’s consistency. The powder was incorporated into liquids to create a much cheaper version of the aristocrats’ chocolate beverage and gained popularity as a confectionary ingredient in a variety of other common recipes (Klein). The invention of the cocoa press and other mass production equipment during the Industrial Revolution thus greatly expanded the use of chocolate and significantly cut production costs to make it available to people across socioeconomic classes.

Solid Form

While cocoa powder was able to mix with water and sugar to create relatively less expensive chocolate drinks and treats, cocoa butter (the other product of the cocoa press) was also able to make chocolate more affordable for the masses. The cocoa butter was initially discarded and amounted to thirty percent wastage (Chrystal and Dickinson); Joseph Fry & Sons recognized that something productive had to be done and manufactured the first chocolate bar in 1847 by returning some of the cocoa butter to their chocolate drink mix to create a paste that could be moulded (Coe and Coe 241). In 1879, Rodolphe Lindt invented the conching machine which further lowered the cost of producing chocolate goods; the machine refined and mixed together cocoa powder, cocoa butter, sugar, vanilla, and dried milk to create a solid chocolate bar that was less expensive and had a smoother texture than that made by Fry & Sons (Presilla 29). When the conching technique was integrated into factory assembly lines during the Industrial Revolution, chocolate bars were able to be produced more affordably on a mass scale, expanding the international accessibility of chocolate. The key ingredient to cheap production was sugar. According to Sidney Mintz, author of Sweetness and Power, sugar developed in parallel to chocolate in that it was a rarity in the 1600s, a luxury by the mid-1700s, and ultimately a staple in Western diet by the mid-1800s (Mintz 78). As the increase in slave labor lowered the price of sugar in the 19th century, the ingredient made its way into more recipes, particularly into chocolate bar recipes as sugar is less expensive than cocoa.

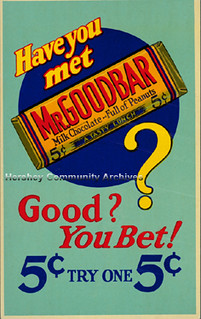

With this new form of solid chocolate, people have been able to consider different ways to make the bar even more affordable. Milton Hersey had experimented extensively with remaking solid chocolate and found that adding a considerable amount of condensed sweetened skim milk to the mixture could create chocolate with a longer shelf life and smoother texture; his relatively cheaper chemical mixture of ingredients was instrumental in delivering chocolate to even more people (D’Antonio 108). Mars was inspired by Hersey’s innovative approach to the chocolate formula and created the Milky Way bar (which uses Hersey’s chocolate) to create a nougat that was similar in taste to but much less expensive than traditional chocolate bars (Brenner 54-55). Both Hersey and Mars were thus able to innovate upon traditional solid chocolate formulas to bring down costs and share chocolate with the masses.

Conclusion

Chocolate has undergone many transformations since its origin as a cacao bean. It began in the liquid form as a type of frothy beverage exclusively for the elite in Mesoamerica and Europe. As the Industrial Revolution took place, new inventions allowed chocolate to transform into a powder that could be made in bulk and used as a confectionary ingredient among the masses. Technological inventions in the years after then reconstructed chocolate into the form of a solid and chocolate makers have continued to develop new recipes and techniques for creating solid chocolate that tastes better and costs less to produce. As such, as chocolate has evolved over time to take different forms, so has its consumer base to mirror the growing popularity and accessibility of the good. From liquid to solid and from royal courts to supermarkets, the evolution of how chocolate can be consumed has allowed it to transcend socioeconomic divides.

Works Cited:

Brenner, Joël G. The Emperors of Chocolate: Inside the Secret World on Hershey and Mars. Broadway Books, 2000.

Chrystal, Paul and Joe Dickinson. History of Chocolate in York. South Yorkshire: Remember When, 2012.

Coe, Michael D. and Sophie D. Coe. The True History of Chocolate, 3rd edition. London: Thames and Hudson, 2013.

D’Antonio, Michael D. Hershey: Milton S. Hershey’s Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006.

Klein, Christopher. “The Sweet History of Chocolate.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 14 Feb. 2014, http://www.history.com/news/the-sweet-history-of-chocolate.

Leissle, Kristy. Cocoa. Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2018.

Mintz, Sidney W. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York, NY: Viking, 1985.

Presilla, Maricel E. The New Taste of Chocolate: A Cultural and Natural History of Cacao with Recipes. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2001.

Multimedia Sources:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/mitko/2213221302/in/photolist-4nzme3-t8L5T-GSvSxv-BSJzZ4-7iwD3k-a5vdvS-j3aNNG-26pYAVs-6aorW7-4nzkzY-j3aLVT-4nvgbB-j38Vgd-4nzjh3-j3ePJw-pghG36-xYeyQ provided the image of the Mayan cacao drinking vessels

https://www.flickr.com/photos/sftrajan/16293258758/in/photolist-tMAaHr-tMp1d6-urBfGu-VJyyts-bWDP85-uJhJuB-tMgBdo-4aBRiv-urKCcC-tMhhcW-tMnaRi-urKL4a-W4RTe7-urDRkW-oompvs-4aMTii-oEzRn1-2cRp1pC-2bCcUyv-xfKVbn-bXuK5J-2aahmmQ-eCkRku-WejGdW-WbLGim-VZki5E-WbLH4j-wXGBeB-xfKVG2-VZkiyq-WbLHEu-2btCvR6-dXsMVL-2bLBtTT-f1Ub3W-wwLTDg-eY2KwR-boKNqs-Nu7Sit-koY1Jd-qPMdbs-7k2sd9-adsFfm-GSk8RS-aT4r6M-icT7jy-9n6wNw-ysp2vh-yGGmQ7-MugYKm provided the image of the European chocolate beakers

https://www.flickr.com/photos/dghchocolatier/8432942639/in/photolist-dRc33K-aQEuPp-dzBtoe-8QXVCB-8R5tLt-di1Wck-xgzo3D-2hv7qhL-eioLo4-659C43-2gWtJg7-6RTBXR-JLP7WU-9pwbPc-9zwaZ2-2irFRt2-rQ1TmC-6rc4zA-69aQa7-4zMFyG-ascr4Y-ascqqQ-dRFFwx-8R1YbN-a1MCpc-8369Q2-3S4Xbf-c7H78U-c7B8uj-23wynFg-23NUdrN-GKU6cu-ascenu-p6rqxG-FeC2ST-24TEHmP-pnVFHg-24TEJSV-24TG5Et-228KTDS-6obUYx-24TEHZx-228KTu3-FeBUwR-FeBTLn-GKU6xj-24PYoGd-24TG4Pk-24TG8DK-228KTpU provided the image of Houten’s mechanized hydraulic press

https://youtu.be/Sg7d7dqZ01U provided the video of cocoa being ground and conched

https://www.flickr.com/photos/26307193@N02/4680253654/in/photolist-88zwmw-88zwuU-88whJ2-73YZfn-VZH83L-baSsQB-88whBg-BVwVF1-88whBK-88whGx-Kandtg-x8pj2Y-aqc6QH-9AdkNM-9CiNVk-9CkjMS-9Ag3EC-cENXtu-nQdpd-9Ad6ax-QLq7uG-JidGHe-QfGZ1S-27F7yWt-qKfz2f-8H2Rac-bVdWPA-2axhNCv-a1TWhV-4yfBa2-6yYHyS-5Bqc7k-rrBZS5-NG5KzV-N4xKwU-BdfckK-9AdknT-9Ad5W2-9sXJWM-2bZrHao-HNpaJo-27gGuzL-9AfZ8f-Z5DRNs-22Wyd5n-VRQjXr-9Agi6G-TDy8AU-9AdkyM-9Ad6dV provided the image of Mr. Goodbar’s advertisement from 1930

For Samuel Pepy’s chocolate was the perfect cure for a hangover, relieving his “sad head” and “imbecilic stomach” the day after Charles II’s coronation. During the life of this great diarist and government official, chocolate drinks passed from being a novelty to being a regular luncheon beverage.

For Samuel Pepy’s chocolate was the perfect cure for a hangover, relieving his “sad head” and “imbecilic stomach” the day after Charles II’s coronation. During the life of this great diarist and government official, chocolate drinks passed from being a novelty to being a regular luncheon beverage.

Codex Féjérvary-Mayer

Codex Féjérvary-Mayer

You must be logged in to post a comment.