Pious Captains of Industry at Home

The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain saw the rise of three Quaker families: Fry, Cadbury, and Rowntree. For a long time, the Quakers were a persecuted religious minority, and as such, they were barred from entering politics. Instead, they applied their industry to great success in business. Particularly, the three aforementioned families became very successful in the chocolate industry, dominating the British markets by the turn of the 20th century (Satre 14). And these Quaker families took their religion seriously, even in their spheres of business. As Coe and Coe note, “Being Quakers, [the three families] had a social conscience in the midst of all this money-making, unlike many other Victorian captains of industry” (250). For example, the families were involved in the antislavery efforts of the 17th and 18th centuries (Satre 14). Seebohm Rowntree and Edward Cadbury gained recognition for studying the terrible conditions of the working class in Britain (Satre 78).

Probably the most notable of the three families was Cadbury. Translating their religious convictions into practice, the Cadburys built a model factory town in the Birmingham suburb of Bournville that included homes, a communal bath, and recreational facilities for the workers; unsurprisingly, the town was a massive success, and the company had to expand its facilities multiple times to cope with the high demand (Coe and Coe 250; Satre 15–16). During a time of ruthless exploitation of the working class, the Quaker families stood out as conscientious capitalists.

However, not all of Cadbury’s actions were without controversy. Most of the Cadbury employees were single women (hired in order to keep the costs low), and many of them were unable to live in Bournville due to the relatively high rent (Satre 16). To them, Bournville was something of a tantalizing paradise. Perhaps a more grievous injury to Cadbury’s reputation occurred during the food adulteration scandal that swept across Victorian era Britain. As the demand for chocolate continued to grow, many confectionaries adulterated their products with cheaper ingredients such as starch and even ground-up bricks. Even Cadbury’s products were shown to have been adulterated with starch and flour. Instead of being apologetic, the company went on the “advertising offensive,” using the slogan “Absolutely Pure, Therefore Best” to claim that only their chocolate was now trustworthy. Questions of hypocrisy or morality aside, the tactic was very successful, helping Cadbury’s to edge out Fry as the preeminent chocolate company in Britain (Coe and Coe 253).

Slavery in Portuguese West Africa

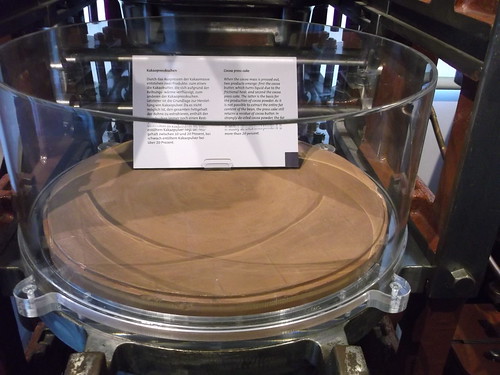

Portugal abolished slavery in 1761, but this decision did not extend to her colonies until 1875 (Satre 33). At the time, São Tomé and Príncipe was a center of cacao production, which constantly required manual labor. And while the supply was outlawed, the demand only kept rising, as chocolate’s popularity continued to grow in Europe and the United States. Thus, the Portuguese devised a new system of “contract labor” called serviçais, which made the workers “free” on paper. The serviçais were to work a specified period of time (often five years) on cacao plantations (roças) with pay, and were supposed to be able to leave after their tenure if they desired.

In reality, the serviçais system was simply slavery reworded. Between 20,000 and 40,000 serviçais slaved away on 230 roças in São Tomé, and another 1,000 worked under the scorching heat on 50 roças on Príncipe (Satre 10). Almost none of the serviçais were ever repatriated, and their contracts were often “renewed” without their input (Satre 11). Furthermore, the children of serviçais were considered to be the property of the plantation owners.

The Seven-Year Wait

William Cadbury (1867–1957) was the grandson of John Cadbury, the patriarch of the family. He was in charge of buying materials for the family business; of course, the key ingredient was cacao. In 1901, while on a business trip to the West Indies, William Cadbury first heard about the presence of slave cacao labor in São Tomé and Príncipe (Satre 18). This disturbing news was then corroborated further when Cadbury’s received an offer for a São Tomé cacao plantation that included the sale of 200 black “laborers” for a sum of money (Satre 18). Given the strong religious convictions of the family, the possibility of Cadbury using slave labor to furnish their products was a dire one, especially given that over 45% of the cacao purchased by the company in 1900 came from São Tomé (Satre 19).

For the next seven years, William Cadbury was involved in a struggle to improve the working conditions of the serviçais, though the process was painfully slow in the eyes of some. Satre also wonders how the Cadburys only heard about the existence of slavery in Portuguese West Africa in 1901, given the extensive evidence available among the Protestant circles by the late 19th century (21). In any case, Cadbury wanted to move slowly, expressing reservations about the veracity of the bill of sale he had received (Satre 19). In 1903, Cadbury traveled to Lisbon to meet with the Portuguese government, who promised that conditions would improve once new regulations passed that year would kick in. More time stalled there, while many doubted the new regulation would have any effect.

Eventually, Cadbury decided to send a representative to travel down to Portuguese West Africa and examine the labor conditions in person. That representative was Joseph Burtt, who arrived in São Tomé in June 1905 and spent two years documenting life on the cacao roças. Burtt returned in 1907, having been convinced of the evils of the serviçais system: “If this is not slavery, I know of no word in the English language which correctly characterises it” (Higgins 137). Even with this piece of decisive evidence, Cadbury spent more time haggling with the British government on whether or not to publicize Burtt’s report. In September 1907, when some called for the boycott of cacao from São Tomé and Príncipe, Cadbury gave a speech opposing the measure (Higgins 137-38). Then, in October 1908, Cadbury decided to visit São Tomé and Príncipe with Burtt, taking stock of the situation himself. Finally, after seven years, Cadbury had made up his mind. His company would boycott cacao grown by slaves in São Tomé and Príncipe.

Between 1901 and 1908, Cadbury still purchased £1.3 million of cacao grown by the sweat and blood of the serviçais in São Tomé and Príncipe. Why did it take Cadbury seven years to decisively act on the information that he knew quite reliably? Perhaps his religious idealism clashed with the realities of running a successful business. Cacao was absolutely vital to the success of his family’s enterprise, and stirring the pot in Portuguese West Africa must not have been an easy move when his company greatly depended on it. Additionally, it was probably easier to apply his religious principles in initiatives in close to home. Whatever the case was, Cadbury has certainly left a complex legacy in the history of chocolate, being at the forefront of progress and reform on certain occasions and dragging its feet at other times.

References

Coe, Sophie and Michael Coe. 2013. The True History of Chocolate. Thames and Hudson. London, UK.

Satre, Lowell Joseph. Chocolate on Trial: Slavery, Politics, and the Ethics of Business. Ohio Univ. Press, 2006.

Higgs, Catherine. Chocolate Islands: Cocoa, Slavery, and Colonial Africa. Ohio University Press, 2013.

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Barrow Cadbury by Thomas Bowman Garvie.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Johannes Vingboons – ‘t eylant St. Thome (1665).jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Packing room, Bournville – Project Gutenberg eText 16035.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

You must be logged in to post a comment.