#ChocolateWasted As We Know It

“Chocolate wasted” was not a hashtag when it first presented itself. As a matter of fact, it was blurted out by a six-year-old actress named Alexys Nycole Sanchez (playing Becky Feder) in Adam Sandler’s Grown-Ups. Per the movie’s storyline, “I wanna get chocolate wasted!” was an appropriate phrase for childlike overindulgence that caught every movie-goer’s attention in 2010 (IMDb). The legendary line even helped Alexys win the “Best Line” category at MTV Movie Awards the following year (IMDb). Soon after, headlines like Los Angeles (LA) Times, celebrities and random college students, like myself, were using the term rather frequently. Still today, there are establishments and products named after the infamous idiom such as a Houston-based ice cream truck and a lipstick shade made by Doses of Color, respectively (Chocolate; Dose of Colors). Amazingly, the power of the Internet allows us to revisit its cinematic origination and locate namesake innovations. But truthfully speaking, the denotation of chocolate wasted is not leading in headlines like its figurative interpretation nor being quantifiable in scholarly publications. Prior to diving into a serious topic, I have several questions that will hopefully heighten your interest to want to learn more.

- What is food waste (including chocolate waste)? What are the associated impacts?

- What are direct implications from chocolate waste throughout the supply chain?

- What qualities does a sustainably certified product uphold? Is waste not included in the sustainability assessment? Does waste not contribute to the overexertion of resources and labor?

- How do I avoid chocolate waste in my home? Does chocolate have an expiration date? Is chocolate (or cocoa) mulch safe for pets?

By Pakeha [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, from Wikimedia Commons

Läderach Chocolate Factory, a Switzerland-based manufacturer, displays a collection of “cocoa waste” in their in-house museum for tourists’ enjoyment. From right to left there: cocoa with waste materials, extracted waste (like stones, dust, metal or wood), and cleaned cocoa.

Food Waste: A Global Problem

On a global scale, 1.3 billion tons of food production meant for human consumption gets lost or wasted annually (FAO). Regarding economic losses, food waste is equivalent to $310 billion in developing countries and $680 billion in industrialized countries with the U.S. leading in food waste and overall wastage than any other country in the world (FAO). Specifically, in the U.S., about 40 percent of food goes uneaten annually which equates to 133 billion pounds with an USD value $161 billion (USDA, n.d.). Conversely, 42 million Americans including 13 million children are facing food insecurity and hunger daily (FAO). Hypothetically speaking, the diversion of 93,000 tons of wasted food could create 322 million meals for people in need and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 714,000 tons (ReFED). This alarming amount of wasted food is not only associated with socioeconomic implications but it also depletes natural resources significantly.

According to Natural Resource Defense Council (NRDC), U.S. food production utilizes the following: 50% of land, 30% of all energy resources, and 80% of all freshwater (Gunders). Resources consisting of land, water, labor, energy and agricultural inputs (fertilizers, pesticides and fungicides) to produce wasted food are squandered as well, unwillingly inviting resource scarcity and negative environmental externalities. Activating ozone pollution, the misuse of agricultural inputs including irrigated water, pesticides and common fertilizers like nitrogen & phosphorus can cause further damage to ecosystems. Irrigation practices promotes water pollution affecting quality, groundwater accessibility, and potable water accessibility (Moss). Moreover, pesticides are common culprits to human health effects, resistance in pests, crop losses, bird mortality and groundwater degradation (Moss). Other inputs, such as nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers, wreak havoc to human health, air quality and aquatic ecosystems (Moss).

The utilization of resources is not the only emitter of greenhouse gas emissions, pertaining to food waste, but also the decomposition of it makes substantial damage to the environment. Postharvest, food waste is the single largest component of municipal solid waste making landfills the third largest source of methane in the country (Gunders). Anthropogenic methane accounts for 10 percent of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions contributing to a rise in global average temperatures, better known as global warming (EPA, n.d.b). Particularly, landfill methane generates 16 percent of total methane releases compared to carbon dioxide which emits 81% annually (EPA). Although carbon dioxide is the main contributor of global warming, methane carries significant weigh as a pollutant due to its ability to absorb more energy per unit mass than any other greenhouse gas (EPA).

Pinpointing on ecological footprint, the most recent “Earth Overshoot Day” occurred on August 2, 2017 in which the extraction of natural resources exceeded the Earth’s capacity to regenerate in the given year (Earth Overshoot Day). By partnering with Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition, Global Footprint Network also reported that a 50% reduction in food waste could push the date of “Overshoot Day” by 11 Days (Earth Overshoot Day).

Chocolate Waste Feeds the Food Waste Problem

The classification of food waste is distinguished by each level of the supply chain including agricultural production, post-harvest handling & storage, processing, distribution and consumption. From a global supply chain perspective, food waste is very difficult to define across countries. The conflicting views of edible versus inedible food waste is one example of cultural variation which impedes the approval of a standardized definition that will cater to all diverse parties and accurately measure waste at the macro level. For instance, the U.S. chocolate market classifies the pulp of a cocoa pod along with the shell of the cocoa bean as inedible products. Thus, cocoa pulp is left at the farmgate level, and at the processing level, cocoa shells are removed and most commonly converted into biofuel or mulch. Unlike the US, the Brazilian chocolate market produces chocolate with cocoa solids but also makes shell and pulp into sellable products such as loose leaf tea or juice, respectively. Moreover, these value-added practices are present-day testaments of indigenous traditions. The myriad indigenous uses of cacao and chocolate products are analogous to the circular economy that we are yearning for today.

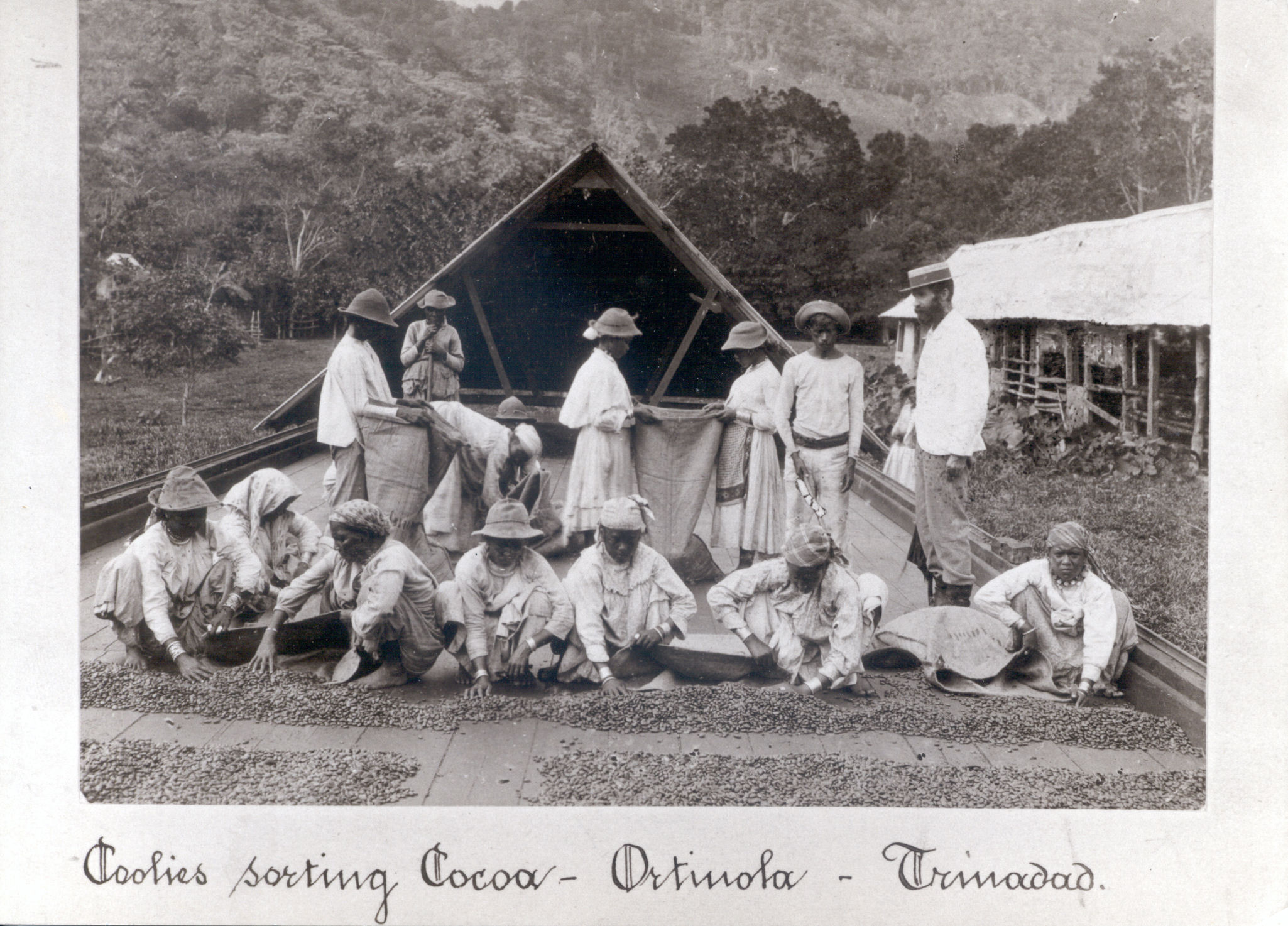

During the Mesoamerican period, chocolate was classified as an esteemed delicacy, a form of payment, ceremonial gift, everyday cooking agent, natural remedy for human health & the environment and so forth. However, during European colonization, the rise of industrialization came with added ingredients, mainly refined sugar, that devalued the quality aspect as well as created a negative image of chocolate over time (Martin, “Sugar”). The health risks of added sugars began to overshadow the medicinal properties of cacao. Even the perception of cacao changed from a specialty crop into a cash crop. From a socioenvironmental view, terroir of cash crops rose in volatility at the extent of mass enslavement and corruption (Martin, “Health”). At the same time, these characteristic flaws did not stop consumption. Even today, popular chocolate products are sugary, highly processed and in conjunction with unethical sourcing backgrounds. For instance, laborers endure labor-intensive work on a daily basis in top cocoa producing countries, such as West Africa. The average laborer is paid below the global poverty line, uses dangerous tools such as a machete to manually cut down cacao pods, applies fungicides & pesticides typically without the proper protective equipment (PPE) and oftentimes exposed to insects and other dangerous animals. In turn, these hazards can result in serious health complications both physically and mentally.

By ICCFO – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

West African laborers removing beans from the cacao pod. It is a labor-intensive process.

Nonetheless, the chocolate market has expanded its portfolio over the years, containing commercial chocolate and craft chocolate, in which consumers can be selective among the two categories. Commercial chocolate is what we usually see in supermarkets in which the supply chain depends on multiple stakeholders (across countries) to meet global demand. Whereas, craft chocolate consists of a relatively small team who produces chocolate in small batches from cocoa bean to bar (Martin, “Haute”). Compared to commercial chocolate, these manufacturers seek to provide quality rather than quantity which typically comes with a higher retail price (Martin, “Haute”).

Once it hits retail, consumers, like myself, are in awe of the multiple offerings, appealing packaging and even sustainability labels that lures us in to help “save the world” and eliminate any guilt from buying chocolate. It’s like a race to find the one with the most honorable mentions comprising of Organic Certified (USDA, Non-GMO and an overlap of third-party ethical standards (Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade, etc.) However, after investigating various sustainability standards, retail chocolate waste is not attributable to certifiable requirements nor is it recognized as a concern overall. Based on logical reasoning and what I stated earlier, the primary ingredients of chocolate consisting of refined sugar, cocoa derivatives (cocoa powder and butter), palm oil and/or milk powder that were extracted from its origination to be processed, transported and packaged as a single product. In addition, these ingredients are combined and further processed into chocolate which is then packaged and transported to retail as a finished good. Just imagine the man hours, natural resources and other inputs used within this supply chain. Broaden that imagination to consider the following: consumers discarding “safe-to-eat” chocolate confections due to fat or sugar bloom, retailers not knowing what to do with an overstock of unsold seasonal products, improper storage temperatures ruining a truckload full of chocolate candies, outdated farming techniques producing more waste than yield and slightly related, the packaging of sustainably certified chocolate causing more harm to the environment than conventional chocolate. The latter, wasteful packaging, is another topic that needs assessment and corrective actions. Unfortunately, these scenarios are real-life examples that are being overlooked and emitting an indefinite amount of greenhouse gases.

In actuality, retailers have the potential to be the main change agents for food waste reduction including chocolate waste. However, edible food is commonly thrown away in these spaces due to excess inventory, imperfections, or damaged packaging. A recent study conducted by the Center for Biological Diversity’s Population & Sustainability and Ugly Fruit & Veg Campaign, reported a grade C or below to most of the top ten grocers in the country including Kroger, Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, Publix and Costco (Center for Biological Diversity). The relatively low grades were based on their poor efforts to address and combat food waste in eight focus areas: corporate transparency, company commitments, and supply chain initiatives, produce initiatives, shopping support, donation programs, animal feed programs and recycling programs (Center for Biological Diversity). Both sustainability driven organizations have pronounced a goal for all U.S. grocery stores to eliminate food waste by 2025 (Center for Biological Diversity). Grocers were also pushed to change their current marketing models into sustainable ones by promoting safer handling and lesser stock levels, leveraging new technologies to strengthen inventory management and creating policies on retail spoilage reduction (Center for Biological Diversity).

By Kgbo – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

A grocer aisle full of chocolate candies wrapped with seasonal packaging.

The Rise of Chocolate Production and Waste

Informatively, consumers worldwide indulge in approximately 7.3 million tons of chocolate every year (Sethi). Developing countries, such as India, Brazil and China, are adopting chocolate products that were once inaccessible or unaffordable for their respective populations (Sethi). Since 2008, disposable incomes for each these emerging markets are increasing exponentially due to economic boost from industrialization (Sethi). The rising market of chocolate products equates to a growing demand for global cocoa and sugar production. Industry experts forecasts a 30% growth in demand, from 3.5million tons of cocoa annually to more than 4.5 million in 2020 (Sethi). In consideration, the amount of chocolate squandered throughout the supply chain is currently undetermined or not shared publicly. Based on noticeable discrepancies in definitions and measurements, chocolate waste and even food waste for that matter will continue to intensify and be discussed loosely unless it’s highly prioritized and welcomes a new branch of international cooperation and mutual accountability. A stride that’s executable if all stakeholders collectively build upon a new systematic approach to carbon neutrality, waste diversion and socioenvironmental benefits.

Chocolate Commonsense

In the meantime, I’ve provided a list of suggestions below that can help you, as a consumer, avoid chocolate waste or divert it to greener waste streams.

- Purchase in moderation.

- Don’t be alarmed by “Sell By Date”. Depending on care and the type of chocolate (milk, dark or white), chocolate is still safe to consume for longer periods of time.

- Chocolate bloom, (whether sugar or fat bloom) which gives off a whitish or light coating on the chocolate’s surface, is still safe for consumption.

- To retain freshness and structure, cool and dark environments are ideal storage locations for chocolate.

- Have an excessive amount of unopened chocolate? Donate to participating charities like Ronald McDonald House Charities and Operation Gratitude.

- ONLY FOR CONSUMERS WITHOUT PETS: Add leftover chocolate or raw cocoa shells, particularly organic certified, in compost for home gardening. *Fyi to pet owners, chocolate is poisonous to dogs and cats due to its theobromine content. If you have pets, you can distribute waste to a composting facility.

- Advocate for chocolate waste (and food waste) assessments from involved stakeholders (including local and national governments, non-governmental organizations [Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade, etc.] retailers, distributors and manufacturers)

By Leslie Seaton from Seattle, WA, USA – Cocoa Mulch, CC BY 2.0.

Cocoa mulch is made out of cocoa shells (most times organic) which are beneficial to soil health. Organic cocoa mulch contains nitrogen, phosphate and potash and has a pH of 5.8 (Patterson). There is also a noticable warning sign to keep dogs away due to theobromine content, which is scientifically proven to be very harmful to pets.

Works Cited.

IMDb. Alexys Nycole Sanchez. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm3465073/?ref_=nmawd_awd_nm

Chocolate Wasted Ice Cream, Co. About Us, 2017. https://chocolatewastedicecream.com/

Dose of Colors. CHOCOLATE WASTED, 2018. https://doseofcolors.com/products/chocolate-wasted

FAO. Food Loss and Food Waste. http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en/

ReFED. A Roadmap To Reduce U.S. Food Waste By 20 Percent, 2016. https://www.refed.com/downloads/ReFED_Report_2016.pdf

Gunders, Dana.“Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill”. Natural Resources Defense Council, Natural Resources Defense Council Issue Paper 12-06-B, 2012, https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/wasted-food-IP.pdf

Moss, Brian.“Water pollution by agriculture”. US National Library of Medicine

National Institutes of Health, 2007, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2610176/

EPA. Methane Emissions. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases

Earth Overshoot Day. Food demand makes up 26% of the global Ecological Footprint, 2018, https://www.overshootday.org/take-action/food/

Martin, Carla D. “Sugar and Cacao”. Chocolate, Culture, and the Politics of Food, 14 Feb 2018, Harvard Extension School, Cambridge, MA. Class Lecture.

Martin, Carla D. “Health, Nutrition, and the Politics of Food + Psychology, Terroir, and Taste”. Chocolate, Culture, and the Politics of Food, 11 April 2018, Harvard Extension School, Cambridge, MA. Class Lecture.

Martin, Carla D. “Haute patisserie, artisan chocolate, and food justice: the future?”. Chocolate, Culture, and the Politics of Food, 18 April 2018, Harvard Extension School, Cambridge, MA. Class Lecture.

Center for Biological Diversity. Checked Out: How U.S. Supermarkets Fail to Make the Grade in Reducing Food Waste. Center for Biological Diversity, 2018, http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/population_and_sustainability/grocery_waste/In-

Sethi, Simran. “The Life Cycle Of Your Chocolate Bar” Forbes. 22 Oct 2017 https://www.forbes.com/sites/simransethi/2017/10/22/the-life-cycle-of-your-chocolate-bar/#42eff5bd66d8

Patterson, Susan. “Cocoa Shell Mulch: Tips For Using Cocoa Hulls In The Garden”, 5 April 2018, https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/garden-how-to/mulch/using-cocoa-hull-mulch.htm

Pakeha. Reinigung von Kakaobohnen.jpg., WikiMedia Commons.7 December 2017, 17:56:47

Kgbo. Easter chocolate in suburban food store in Brisbane, Australia in 2018.jpg, WikiMedia Commons, 24 February 2018, 10:04:29

Seaton, Leslie. Cocoa Mulch (4051611349).jpg, WikiMedia Commons, 20 October 2009, 15:55

ICCFO. Cocoa farmers during harvest.jpg. WikiMedia Commons, 1 January 2015,

You must be logged in to post a comment.