In a city square home to L.A. Burdick Chocolates and Cardullo’s Gourmet Shoppe, one would not necessarily first select CVS for the purpose of purchasing chocolate products. However, as I commenced my chocolate crawl of Cambridge to analyze chocolate displays around Harvard Square, I realized I did not need to venture any further than CVS to encounter a chocolate emporium. Although CVS exhibits a vast variety of chocolate products, ranging from mass-produced, “Big 5” chocolate brands to more premium, craft chocolate brands, to appeal to consumers’ differing taste preferences and criteria for selecting and purchasing chocolate, I would contend that CVS more adeptly encourages consumers to purchase chocolate products through an economically-based methodology. In particular, by targeting consumers’ economic sensibilities through the prominent display and advertisement of sale prices and ExtraBucks reward promotions, CVS draws upon consumers’ desire to mitigate indulgent, “impulse buys” of chocolate products by emphasizing the sound economic advantages that result from purchasing their store’s chocolate products.

Before analyzing CVS’ economic methodology, it is productive to first provide a report of my field study’s findings on the CVS store located at 6 JFK Street. After entering CVS, I discovered that two of the four aisles on the store’s first floor are replete with chocolate. Aisle 3, which is labeled as “Bagged Candy” and “Candy,” contains shelf after shelf of chocolate products, most of which hail from the Big 5 chocolate companies. Colloquially known at the “Big Five,” Nestle, Mars, Cadbury, Hershey’s and Ferrero represent the largest chocolate companies in the world today (Martin and Sampeck 2016: 50). Along the shelves of Aisle 3 were products manufactured by Hershey’s, Nestle, Cadbury, and Mars in all varieties and size combinations, which ranged from multipacks of individually wrapped fun size bars to resealable snack packs to individual bars. The varying quantities of these packages indicate that consumers desire different size combinations, according to their particular needs and interests. For example, one consumer might be seeking a personal snack while another consumer might be interested in buying a multipack to share with other people.

In addition to the plethora of chocolate products available to consumers, the shelves of Aisle 3 also provide evidence of CVS’ economically-based marketing strategy: emphasis on sales and future monetary rewards. As part of its company, CVS promotes a customer rewards program, the ExtraCare program (https://www.cvs.com/extracare/home). Based upon their purchases at any CVS location, members of the ExtraCare program will receive ExtraBucks, a coupon with a monetary amount that can be applied to a future purchase. In the case of Aisle 3, certain chocolate products were eligible for both a sales promotion and ExtraBucks rewards. Bright yellow tags, which dangled from the aisle’s shelves, advertised that one could purchase 2 chocolate products at the reduced price of $6 and that such a purchase would generate $1 in ExtraBucks.

After this close observation of Aisle 3, I rounded the corner to Aisle 4 and encountered a continuation of chocolate displays. In particular, Aisle 4, the “Seasonal” aisle, featured displays of chocolate products and other candy items, mostly from the Big 5 brands, that were packaged and labeled for Easter, a holiday that occurred the weekend prior to this field study. These seasonal products disclose the marketing tactics of the Big 5 chocolate companies, which rebrand their products with special shapes (e.g. eggs), pastel packaging, and images synonymous with Easter (e.g. chicks and bunnies). The contents of Aisle 4 also underscored the vast quantity of chocolate on the market: even after the celebration of Easter, a holiday culturally-associated with the purchasing of candy and chocolate to fill Easter baskets, CVS still possessed a glut of Easter-specific chocolate products.

For the purposes of this field study, I also noticed the continuation of sales prices and economic incentives in Aisle 4. Larger, bright yellow tags placed perpendicular to the aisle’s shelves announced that the entirety of Aisle 4’s items were on clearance and 50% off. Although many of the chocolate products in Aisle 4 were exactly identical in taste and quality to those of Aisle 3—a Reese’s seasonal, egg-shaped candy has the exact same taste as a Reese’s peanut butter cup—the store granted the Easter products a special sale price because their packaging was no longer relevant and, more importantly, was no longer a compelling factor to make consumers purchase those particularized, Easter-appropriate items. Therefore, the economical advantage, rather than the packaging or seasonality, of purchasing these Easter chocolate products emerged as the chief marketing tool utilized by CVS to encourage consumer purchase.

On the whole, my field study sensitized me to the pervasiveness of CVS’ sales tactics with regard to chocolate purchases. Indeed, the sales, discounts, and monetary rewards associated with the purchase of chocolate products extended well beyond the chocolate-specific aisles, Aisle 3 and Aisle 4. In meandering around the first floor, I also discovered two chocolate display cases that were distinct and separate from the aisles: a Brookside chocolate display and a “Premium Chocolates” display. Both displays consisted of a pop-up cardboard structure placed at opposite ends of Aisle 2, a strategic juncture that could, in turn, attract a consumer’s attention as he or she moved between or along aisles. The Brookside display seemed to align well with the contents of Aisle 2, the “Grocery” aisle, since it featured snack-type chocolate products, such as “Crunchy Clusters,” chocolate-covered almonds, and chocolate-covered dried fruits. In addition to these items, the Brookside display also featured bright yellow tags that announced the special rate of 2 chocolate products for $6.

In contrast to the snack-packaging of the Brookside display, the Premium Chocolate display included mostly individually-packaged bars from Lindt, Ghiradelli, Ferrero Roche, and Chuao, among other premium brands. Even those these brands were specially labeled as “premium” and therefore associated with luxury and higher cost, the “Premium Chocolate” display also featured the same bright yellow sales tags, which advertised the special rate of 2 chocolate bars for $5. Therefore, just as ubiquitous as the presence of chocolate products on the first floor of CVS was the presence of sales tags and special rates for chocolate products—the sales pricing did not discriminate based on chocolate quality but rather applied to Big 5 brands and premium brands alike.

Even if I had somehow managed to avoid the two aisles or two prominent displays of chocolate on the first floor, this CVS store ensured that I, along with every consumer, would encounter chocolate while waiting in line to make a purchase. On both the first floor and second floor, this CVS store possesses checkout lines, each of which is replete with shelves lined with individual candies and chocolate bars. The presence of chocolate in the CVS store is inextricably bound with the promise of savings: the individual chocolate bars at the checkout areas also benefited from sales promotions: 2 individual chocolate bars or candies for $3.

After completing my observational field study of this particular CVS location, I conducted research into CVS as a company. CVS, which stands for Consumer Value Stores, opened its first store in Lowell, Massachusetts in 1963; this first store exclusively sold health and beauty products (https://www.cvshealth.com/about/company-history). Although CVS brands itself as a pharmaceutical store, it has developed far beyond its origins as purely a purveyor of health and beauty products. Inherent to the company’s expansive, national growth has been its acquisition of other competing stores throughout the United States. As part of this nationalization of CVS as a franchise, CVS has also worked to secure consumer loyalty, especially through its emphasis on providing value to customers. In fact, CVS was the first national pharmacy retailer to launch a loyalty card program, the ExtraCare Card, which it established in 2001(https://www.cvshealth.com/about/company-history). Therefore, an understanding of CVS’ company history demonstrates its focus and commitment to consumer value, which it achieves through the employment of sales prices, special discounts, and ExtraCare membership rewards.

Based upon my field study of the Harvard Square CVS store and a fuller understanding of the CVS company history and programming, I derived a few salient impressions about CVS in relation to its marketing and selling of chocolate products.

CVS possesses a keen understanding of the current landscape of the chocolate market with regard to consumer taste, interests, and needs. According to Heike C. Alberts and Julie Cidell, the United States has been experiencing a “chocolate revolution” during the last few decades: American consumers have expanded their chocolate consumption “beyond traditional mass-market chocolate such as Hershey’s” and the other Big 5 companies to include “more premium chocolates…and more dark varieties” (Alberts and Cidell 2016). Stores like CVS have responded to meet this shift in taste among American consumers by stocking more premium chocolate brands, including European brands. Although European chocolates were “largely limited to specialty food stores and import stores” a few decades ago, European brands like Milka, Ritter Sport, and Lindt are now “available in many grocery stores, department stores such as Target and Walmart, and drugstores such as Walgreens and CVS” (Alberts and Cidell 2016). Although much of the CVS chocolate selection in Aisles 3 and 4 belongs to traditional mass-market chocolate brands, such as the Big 5 companies, the inclusion of brands like Lindt in the Premium Chocolate display at the Harvard Square CVS attests to the entrance of European brands into American markets and its increasing availability among these markets to include pharmacy stores like CVS.

In addition to Americans’ burgeoning interest in European chocolates and premium brands, American consumers have also begun to consider the social and ethical components of chocolate products. In response to the various ethical facets of cacao production, such as labor conditions, compensation, etcetera, many American consumers have been drawn to the fine chocolate market, which exhibits a “resistance” characterized by “a group force or momentum to link sensual enjoyment with ethical concern” (Martin and Sampeck 2016: 52). The fine chocolate market has been utilizing strategies, such as certification programs like Direct Trade and FairTrade, to demonstrate their companies’ commitment to rectifying social injustices. Such campaigns and endorsements speak to consumers’ desires to enjoy chocolate in an ethically and socially-conscious manner. For example, Endangered Species Chocolate, one of the brands available in the “Premium Chocolates” display of the Harvard Square CVS store, promises to donate 10% of net profits to its GiveBack Partners that help wildlife and endangered species (http://www.chocolatebar.com/?page_id=18). Thus, as observed at the Harvard Square CVS, CVS recognizes the differing tastes of chocolate consumers—brand name, perceived quality of products, and socially-conscious choices—and seeks to cater to their customers by selling a varied selection of products that will meet these consumer preferences.

In addition to recognizing the need to meet consumers’ broad spectrum of tastes, CVS also utilizes psychology to attract customers and promote chocolate purchases. In primarily pharmaceutical stores like CVS, the average customer does not necessarily visit with the express purpose of purchasing chocolate. Instead, chocolate purchases at CVS can be classified as “impulse buying,” which may be described as a spontaneous purchase bought “without thoughtful consideration why and for what reason a person should have the product” (Fennis and Stroebe 2010: 274). For example, CVS’ placement of its chocolate products at the checkout areas on both the first and second levels capitalizes upon this psychological understanding of consumer behavior because “chocolate bars and other tempting sweets are often displayed near the checkout counter when customers are distracted by thoughts about paying for their purchases” (Fennis and Stroebe 2010: 275).

In addition to encouraging a psychological response of impulse buying, CVS strategically situates chocolate displays to capitalize upon knowledge of the scientific, neurological basis of consumer behavior. In other words, CVS utilizes its displays as visual stimuli that can activate the neurological systems that motivate customers to purchase chocolate products. A 2014 scientific study entitled “Neural predictors of chocolate intake following chocolate exposure” utilized neuroimaging technology to verify how exposure to chocolate stimuli can predict the subsequent intake of chocolate (Frankort et al. 2014). In this study, participants were exposed to the smell of chocolate over the period of an hour and then shown images of chocolate (Frankort et al. 2014). Neuroimage results of this exposed group revealed that the brain regions involved in food reward, including the amygdala, striatum, hippocampus, insula, ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra, were activated by these external stimuli of chocolate and directly correlated with the later consumption of chocolate (Frankort et al. 2014). In essence, “neural correlates predict subsequent behavior (i.e. chocolate intake)” (Frankort et al. 2014). Based on such scientific evidence, there is a demonstrated neurological basis for chocolate consumption, which can be stimulated by external cues like the time of day and place (Benton 2004: 215). Therefore, customers at CVS who are stimulated by visual stimuli like chocolate displays have a greater likelihood of subsequently purchasing and consuming chocolate.

While these scientific and psychological aspects underlying consumers’ chocolate purchases are certainly important factors acknowledged and employed by CVS in its marketing strategy, I would contend that CVS utilizes economic incentives as the primary means of convincing customers to purchase chocolate.

This economic component complements and augments the psychology of chocolate purchasing. In particular, scientists and psychologists have determined that the phenomenon of impulse buying is “more likely for low priced products” (Fennis and Stroebe 275). Many of CVS’ chocolate products could be considered “low priced products” because they were part of a special sales promotions (2 for $6) and/or associated with the acquisition of future money-off coupons ($1 in ExtraBucks). As a result of transforming their chocolate products into low priced products through the use of economic marketing strategies, CVS increases the motivation of customers to act upon their psychological response of impulse buying. CVS’ use of economical savings as a marketing strategy to increase chocolate purchases proves a psychologically-astute method. Scientists have demonstrated that the “control motivation” consumers might attempt to exercise to prevent impulse buying is lowered when “the desirable items are not very expensive” (Fennis and Stroebe 2010: 275). In other words, consumer satisfaction resulting from saving money and making economically-sound purchases overpowers their control motivation and mitigates feelings of guilt that consumers might experience in buying chocolate products, which are often classified as luxurious, indulgent items. CVS makes luxury chocolate products, especially “premium” chocolate brands from Europe or brands with socially-conscious values, affordable to the masses.

In the broader historical context, chocolate has been inextricably bound with economics and social class. After its introduction to Europe, chocolate was primarily enjoyed by European elites; however, changes in the 1800s resulted in a broadening of the availability of chocolate. Due to the industrialization of food, including massive mechanization, retailing, and transportation changes, chocolate transformed from “an elite, expensive product” to “an inexpensive…low-cacao-content chocolate bar to be consumed as a food by elite and non-elite alike” (Martin and Sampeck 2016: 50). Given this democratization of chocolate, chocolate producers had to meet this new, increased demand, and, as a result, “large chocolate manufacturers became the producers of the majority of the world’s chocolate” (Martin and Sampeck 2016: 50). Chocolate became an industry that needed to market to different social sectors. Due to chocolate’s historical and intrinsic connection with socioeconomic class, CVS’ economically-based approach of sales prices, discounts, and other monetary incentives emerges as a very efficacious method for appealing to the different social statuses of customers.

In summary, this field study of the Harvard Square CVS store reveals the varying tactics and approaches a retail store may employ to encourage the purchase of chocolate products. While visual stimuli, such as chocolate displays, store layout, variety of products, and other tools may be utilized to promote chocolate purchasing, CVS employs an efficacious economic model to increase its chocolate sales. Truly hearkening to its roots as a Consumer Value Store, CVS convinces its customers that they can have their chocolate at a cost-effective price and eat it, too!

Sources:

Alberts, Heike C. and Julie Cidell. 2016. “Chocolate Consumption, Manufacturing, and Quality in North America and Europe.” In The Economics of Chocolate, edited by Mara P. Squicciarini and Johan Swinnen, 119-133.

Benton, David. 2004. “The Biology and Psychology of Chocolate Craving.” In Coffee, Tea, Chocolate, and the Brain, edited by Astrid Nehlig, 205-216.

Fennis, Bob M. and Wolfgang Stroebe. 2010. The Psychology of Advertising.

Frankort, A. et al. 2015. “Neural predictors of chocolate intake following chocolate exposure.” Appetite 87: 98-107.

Martin, Carla and Kathryn Sampeck. 2016. “The Bitter and Sweet of Chocolate in Europe.” Presented at The Social Meaning of Food Workshop, The Institute for Sociology, Centre for Social Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, June 16-17, 2015, Budapest, Hungary.

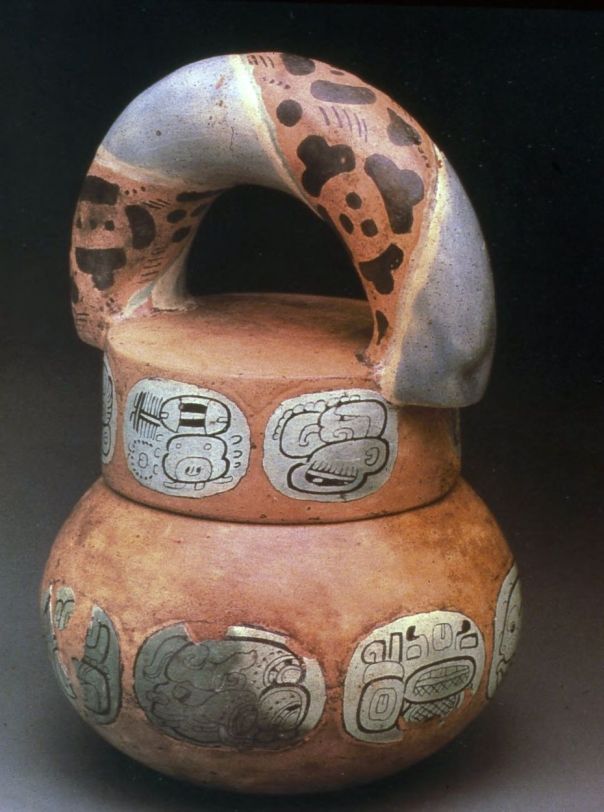

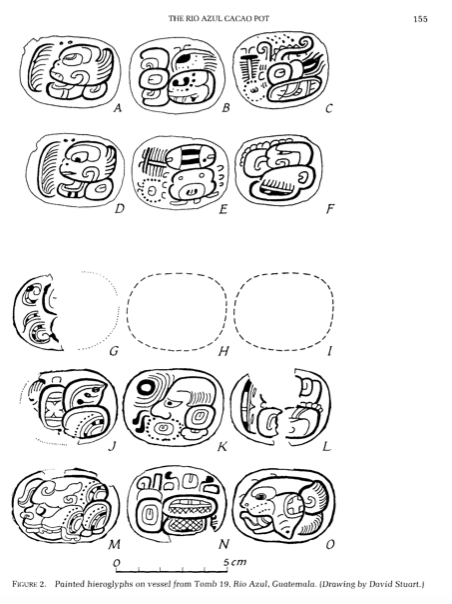

The Río Azul vessel features an exterior surface, which has been covered in stucco and adorned with Classic Mayan hieroglyphs. Close analysis of the vessel’s exterior can provide invaluable insights into the Classic Mayan artistic tradition, writing system, artisan class, manufacturing process, etcetera.

The Río Azul vessel features an exterior surface, which has been covered in stucco and adorned with Classic Mayan hieroglyphs. Close analysis of the vessel’s exterior can provide invaluable insights into the Classic Mayan artistic tradition, writing system, artisan class, manufacturing process, etcetera. This view allows one to see the “lock-top” feature of the Río Azul vessel’s lid. One can discern the grooves into which the vessel’s lid slid and closed, which prevented the vessel from spilling its liquid contents.

This view allows one to see the “lock-top” feature of the Río Azul vessel’s lid. One can discern the grooves into which the vessel’s lid slid and closed, which prevented the vessel from spilling its liquid contents.

You must be logged in to post a comment.