Introduction

Despite the variety of available chocolate products, the process by which a chocolate bar comes to fruition maintains certainty consistency. A ubiquitous procedure, the evolution of a cacao pod to a chocolate bar ought to have reached contemporary standards of ethicality and efficiency. Yet, the bean-to-bar progression is plagued with inherent injustices that have been embedded in the chocolate industry from the start. Fundamental to the development of capitalism, cacao, a commodity crop like tobacco, sugar, coffee, rum, and cotton, initially relied heavily on the slave trade to fuel increasing demand. (Martin, 2017) Yet, despite the abolition of slavery in the mid 19th century, modern day slavery still prevails in the cacao industry. In response to the persistent pervasiveness of injustices in the bean-to-bar process, particularly surrounding the harvesting and cultivation of cacao, bean-to-bar brands have proliferated as a potential solution with a commitment to both the ethicality and culinary aspects of chocolate production; Taza Chocolate in Somerville, Massachusetts typifies one of these companies striving to produce palatable chocolate through ethical practices and a high degree of production transparency.

Cacao-Chocolate Supply Chain

The cacao-chocolate supply chain begins with the cultivation of cacao pods. After cacao cultivation, the pods are harvested and the seeds and pulp are separated from the pod. The cacao seeds are then fermented and dried before being sorted, bagged, and transported to chocolate manufacturers, chocolate makers, and chocolatiers. The cacao beans then undergo roasting, husking, grinding, and pressing before the product undergoes a type of “polishing,” called “conching,” in which final flavors develop. (Martin, 2017) Differences in the execution of each step influence the ultimate taste, texture, feel, and consistency of the chocolate bar.

Today, cacao cultivation and harvesting has predominately shifted away from the Americas to West Africa. Almost all of the world’s cacao used in the making of chocolate, approximately 75%, grows in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana. (Martin, 2017). Despite the shift of the geographic foci of cacao trade, partially fueled to escape slavery associated with commodities crops in the Americas, a narrative of slavery and exploitation continue to plague the cacao trade. (Martin, 2017) Modern day farming of cocoa has exploited child and migrant labor, with price fixing by governments a likely causal link between abuses and the need for farmers to reduce their own cost. (“Organic Cocoa Industry” 2014) Additionally, as small producers, the farmers lack collective bargaining ability and are thus dependent on price fixing governments or commodity boards that “leave them at the mercy of independent traders or other large buyers of their cocoa.” (“Organic Cocoa Industry” 2014)

Approximately two million small, independent family farms in modern day West Africa produce the vast majority of cacao. Each farm, between five to ten acres in size, collectively produce more than three million metric tons of cacao per year. (Martin, 2017) While some of the farms also grow crops like oil palm, maize, and plantains, to supplement their income, the average daily income of a typical Ghanaian cacao farmer hovers between $0.50-$0.80. (Martin, 2017).

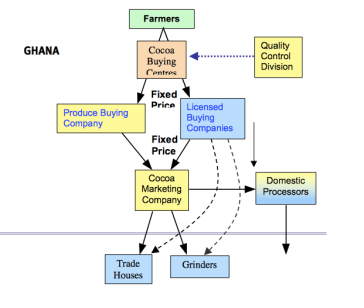

The current system of buying and selling cacao in West Africa typically involves the growers and farmers selling to intermediaries, who subsequently sell upstream to additional intermediaries. The longer the supply chain, the greater opportunity for corruption and the exploitation of the farmers as the latter receive increasingly smaller shares of the overall price of a chocolate bar as the supply chain grows more layered with intermediaries adding their own profit layer. The marketing structures in Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire, the two largest cacao producers in West Africa, typify West African cacao trade. In Ghana, farmers take cacao to buying centers operated by the Ghana Cocoa Board, Cocobod. Cocobod fixes prices, and either Cocobod representatives or private buyers purchase the cacao. In Cote d’Ivoire, private traveling buyers collect cacao from farmers and pay a guaranteed minimum export price. (“Organic Cocoa Industry,” 2014)

The marketing structures in both countries exemplify the complexities of the exploitation of cacao farmers. In Ghana, local elites dominate cacao farming. Raising cacao prices would empower the local elite, and threaten the state. (Martin, 2017). Therefore, the state, by controlling cacao prices through the Cocobod, also controls and restricts the power of the local elite. In Cote D’Ivoire, peasants comprise the majority of cacao farmers, and consequently, present a lesser threat to the government of the Cote D’Iviore. Consequently, allowing itinerants to collect cacao from farmers, while giving peasant farmers more ability to negotiate prices and thus greater power, does not, in the government’s view, create a threat to the state.

Cacao, a commodity, theoretically should command a volatile price as determined by the global markets. Market variability within the past half-decade, however, has demonstrated the effects of a long cacao-supply chain. Due to farming conditions, over the past five years, cacao supply has gone from a severe deficit to a surplus. In late 2014, poor harvest yields coupled with increased demand for chocolate drove the supply of cacao way down. (Ferdman, 2014) In fact, a 2014 Bloomberg report even suggested that in 2020, when the demand for cacao would exceed supply by 1 million metric tons, the world would have to turn to a genetically modified form of cacao, even at the forfeit of flavor, to attempt to meet demand. Yet, despite market economics which dictate that with increasing scarcity an item should demand a higher price, unusually, cacao farmers struggled to make a profit and began switching to other crops like palm and rubber. (Ferdman, 2014). Profits from the higher prices, instead of trickling down to the farmers, were captured higher up the supply chain. As recently as March 2017, however, cacao supply had usurped demand. Rather than let the market reset the pricing of cacao, the governments of both Cote D’Ivoire and Ghana announced an unspecified cut in prices of cacao, which further economically harms the farmers. With only meager profits, and constant subjection to harsh work conditions, the farmers cannot move beyond subsistence level and suffer from inescapable exploitative labor practices. (Hunt & Aboa, 2017)

In response to the social and economic injustices associated with the cacao-supply chain, various organizations—governmental, non-governmental, global and national—have been established with the common mission of improving ethicality and corporate responsibility of global cacao practices. For example, the International Cocoa Organization, ICCO, ratified by the United Nations, unifies cacao producing and cacao consuming countries. The ICCO established an official mandate on a Sustainable World Cocoa Economy to addresses the exploitative environment cacao farmers face. (“International Cocoa Organization”) In 2012, Cargill, an American global corporation with a large focus on agricultural commodities, founded Cargill Cocoa Promise which specifically concentrates on bringing transparency to the global cocoa supply chain by supplying ethically sourced cacao to their buyers. (“Cargill is committed to helping the world thrive” 2017) On a micro, private level, Cargill itself develops professional farmers’ organizations in the regions from where the corporation buys cacao in order to help farmers develop a sustainable way to improve and maintain their livelihoods.

Further, various organizations have established criteria for certifications with the goal of enticing companies to comply with specified ethical requirements in exchange for public acknowledgement for doing so. “Fair Trade,” a designation granted by the nonprofit of the same name, stands out as a recognizable stamp on many shelf-brands. Self-defined as an organization which “enables sustainable development and community empowerment by cultivating a more equitable global trade model that benefits farmers, workers, consumers, industry and the earth,” Fair Trade certifies transactions between U.S. companies and their international suppliers to guarantee farmers making Fair Trade certified goods receive fair wages, work in safe environments, and receive benefits to support their communities. (“Fair Trade USA,” 2017) Yet, while in theory Fair Trade seems to address many issues the cacao farmers face, critics of the certification point out there exists a lack of evidence of significant impact, a failure to monitor Fair Trade standards, and an increased allowance of non-Trade ingredients in Fair Trade products. (Nolan, Sekulovic, & Rao 2014) So, while in theory certifications like Fair Trade offer the potential to improve the cacao-supply chain by ensuring those companies who subscribe to the certification meet certain criteria, the rigor and regulation of the criteria appears debatable.

Contemporary Solutions: Bean-to-Bar Chocolate

In contrast to the traditional process of chocolate manufacturers buying beans in bulk from suppliers who amalgamate beans from anonymous farms, “bean-to-bar” companies offer another potential solution for the injustices in the bean-to-bar process. By maintaining absolute control of the bean-to-bar process by cutting out the middle-men and dealing directly with the cacao farmers, these small companies not only strive for superior quality, but commit to ethical standards. (Shute 2013) The hope is that the the bean-to-bar “pipeline will make for more ethical, sustainable production in an industry with a long history of exploitation.” (Shute, 2013) The expensive price tag associated with a small-batch bean-to-bar product contributes to a more decent wage for West African cacao farmers, while simultaneously promising an excellent product.

The close relationship proves to be mutually beneficial as the bean-to-bar companies get well-flavored chocolate and the cacao farmers receive fair wages. (Zusman, 2016) Further, the transparency associated with the small-batch bean-to-bar process motivates the companies to adhere to ethical criteria, as well as keep up to date on ethical practices, and encourages the cacao farmers to take extra care in drying and fermenting their beans. Some bean-to-bar chocolate companies have also started following the lead of coffee companies by implementing Direct Trade, a partnership arguably doing more, directly, to help minimize exploitative practices, than Fair Trade. (Zusman 2016)

Direct Trade, a type of product sourcing, partners bean-to-bar buyers directly with cacao farmers. While providing some oversight on ethical practices, Fair Trade’s supervisory capacity does little to create a more direct relationship between the farmers and the ultimate producers or to eliminate extraneous intermediaries diluting profit from the growers. Further, achieving a Fair Trade certification costs between US$8,000 and US$10,000. In contrast, Direct Trade costs the chocolate bar producer nothing while facilitating their purchase of cacao directly from farmers. This one-step connection, perhaps the epitome of the bean-to-bar movement, allows the buyer and seller (the farmer) to together dictate fair prices, and ensure the cacao farmers receive fair wages, working conditions, and support. With control over the bean-to-bar pipeline, and Direct Trade making such a choice more accessible, these smaller chocolate bar companies seem to provide a more viable blueprint to mitigate, and hopefully end, the exploitation of the cocoa farmers.

Taza Chocolate

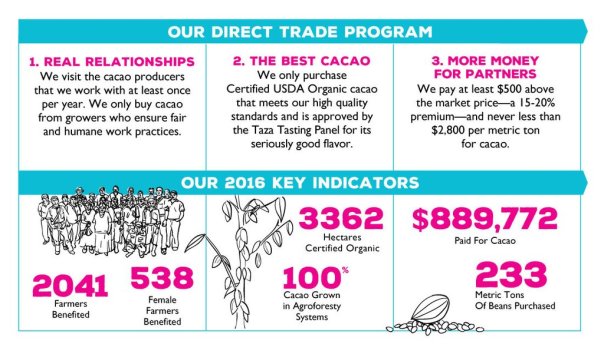

Alex Whitmore, an innovator of the bean-to-bar chocolate movement founded Taza Chocolate in 2005. A ground-breaking chocolate shop committed to “simply crafted, but seriously good” chocolate, Taza exists as “a pioneer in ethical cacao sourcin.” (“Organic Stone Ground Chocolate for Bold Flavor” 2017) Taza “created the chocolate industry’s first third-party certified Direct Trade cacao sourcing program, to ensure quality and transparency for all.” (“Organic Stone Ground Chocolate for Bold Flavor” 2017) Taza maintains a direct “real, face-to-face relationships with growers who respect the environment and fair labor practices,” and pays farmers a premium for cacao well above the Fair Trade price. (“Organic Stone Ground Chocolate for Bold Flavor” 2017) Within this symbiotic relationship, in exchange for ethical treatment and the removal of middlemen, the cacao farmers provide Taza with the “best organic cacao.” (“Organic Stone Ground Chocolate for Bold Flavor” 2017)

Taza maintains a high degree of transparency on their website. In addition to publishing their Direct Trade Program Commitments (“1. Develop direct relationships with cacao farmers; 2. Pay a price premium to cacao producers; 3. Source the highest quality cacao beans; 4. Require USDA certified organic cacao; 5. Publish an annual transparency report” (“Organic Stone Ground Chocolate for Bold Flavor” 2017) ), Taza provides hyperlinks to their transparency report, cacao sourcing videos, and their sustainable organic sugar. Seemingly, Taza exemplifies the archetype bean-to-bar company.

I spoke with Ayala Ben-Chaim, Taza’s Tours and Events Coordinator, to gain further understanding of Taza’s revolutionary approach and the impact Taza has on the cacao-chocolate supply chain. Ayala explained that Alex set out with the goal of creating a socially responsible chocolate brand that balanced environmental, social, and quality responsibilities. In 2005, market trends indicated consumers wanted organic products, so Alex initially considered making chocolate that was organic and Fair Trade. Ayala noted, however, that as Taza began to develop, Alex discovered not all organic products aligned with Fair Trade certified products, not all Fair Trade Products aligned with organic products, and occasionally both organic and Fair Trade products tasted poorly. Additionally, early on, Taza did not have the budget to pay for Fair Trade certification; further, Alex realized he could be paying that fee directly to the cacao farmers. Consequently, Alex turned to the idea of direct trade.

Taza identified the main issue with the cacao-supply chain as the length of the chain from farmer to chocolate company. The longer the supply chain, the more opportunity for funding to disperse before reaching farmers, and the more opportunity for corruption by middle-men. Confirming the information I found on the website, Ayala explained that to help combat the supply chain injustices by shortening the cacao-supply chain as much as possible, Taza adopted Direct Trade. Ayala elaborated that, emulating Counter-Culture coffee, an organic coffee company that formalized a third-party direct trade policy, Alex forfeited Fair Trade in favor of Direct Trade, and Taza hired a cacao sourcing manager. (“Sustainability At Coffee Origin,” 2017) Based in Columbia, the sourcing manager oversees all of the cacao sourcing, visits cacao farms regularly to ensure the conditions meet Taza’s own highly ethical criteria, and that the cacao fetches fair prices. One of Taza’s biggest direct trade sourcing successes was creating a relationship with Haiti. Taza consistently pays farmers significantly more under the Direct Trade policy than they would have received under a Fair Trade certification, which would not have necessarily cut out middlemen.

Ultimately, however, the question remains whether the extreme efforts Taza puts forth to create an ethically sound product really produce a significant impact on the cacao-supply chain. Although Taza makes a significant impact on the people with whom they directly partner, Ayala commented that many customers approach her to ask about Fair Trade and completely confuse Direct Trade for Fair Trade, and thus do not comprehend Fair Trade’s shortcomings and the increased benefits to the farmers of Direct Trade. Although frustrating, she does concede that some level of awareness in the choice of which chocolate to purchase is better than a total lack of knowledge or concern.

Ayala offered the statistic that in 2005, Taza was only one of three bean-to-bar chocolate companies. Today, however, Taza is one of 60 bean-to-bar companies. While the significance of Taza’s impact may be relatively small, the overall bean-to-bar movement has started to gain momentum. If each bean-to-bar company identifies issues in the cacao supply chain similarly to Taza, then, over time, an increasingly larger percentage of chocolate will come from ethically responsible sourcing. And, hopefully, that will also mean that customers will start to become more knowledgeable about what they are eating, become more discerning about the distinctions between the various “stamps” on the packaging, and more willing to pay a higher price for product that subscribes to and supports ethical farming.

Bean-to-bar chocolate companies appear to be a viable potential solution, albeit slow and on a more micro level, to addressing the issues in the cacao-chocolate supply. Because currently the consumer base does not seem to possess a critical awareness of different certifications, the bean-to-bar companies must continue to pioneer more moral standards until enough customers catch up and until demand forces the bigger chocolate venders to take a similar approach. Until then, tackling the exploitation embedded in the cacao-supply chain falls exclusively on the shoulders of the chocolatiers equally loyal to both chocolate and social responsibility.

References

“Cargill is committed to helping the world thrive.” Provider of food, agriculture, financial and industrial products and services to the world. | Cargill. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017.

Fair Trade USA. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017.

Ferdman, Roberto A. “The World’s Biggest Chocolate-maker Says We’re Running out of Chocolate.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 15 Nov. 2014. Web. 27 Apr. 2017. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/11/15/the-worlds-biggest-chocolate-maker-says-were-running-out-of-chocolate/?utm_term=.6f1b2516fded>.

“International Cocoa Organization.” About ICCO. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017.

Leissle, Kristy. “Cosmopolitan Cocoa Farmers: Refashioning Africa in Divine Chocolate Advertisements.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 24.2 (2012): 121-39. Web.

Nolan, Markham, Dusan Sekulovic, and Sara Rao. “The Fair Trade Shell Game.” Vocativ. Vocativ, 16 Apr. 2014. Web. 03 May 2017.

“Organic Cocoa Industry.” Cocoa Production and Processing Technology (2014): 67-78. Anti-Slavery International. Web.

“Organic Stone Ground Chocolate for Bold Flavor.” Taza Chocolate. N.p., 2015. Web. 27 Apr. 2017. <https://www.tazachocolate.com/>.

Martin, Carla. “Modern Day Slavery.” Lecture, Chocolate Lecture, Cambridge, March 22, 2017.

Martin, Carla. “Alternative Trade and Virtuous Localization/Globalization.” Lecture, Chocolate Lecture, Cambridge, April 04, 2017.

Martin, Carla. “Slavery, Abolition, and Forced Labor.” Lecture, Chocolate Lecture, Cambridge, March 01, 2017.

Schatzker, Mark. “To Save Chocolate, Scientists Develop New Breeds of Cacao.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 14 Nov. 2014. Web. 27 Apr. 2017. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-11-14/to-save-chocolate-scientists-develop-new-breeds-of-cacao>.

Shute, Nancy. “Bean-To-Bar Chocolate Makers Dare To Bare How It’s Done.” NPR. NPR, 14 Feb. 2013. Web. 03 May 2017.

“Sustainability At Coffee Origin.” Counter Culture Coffee. N.p., 27 Feb. 2017. Web. 03 May 2017.

Taza Chocolate. “Sourcing for Impact in Haiti.” Vimeo. Taza Chocolate, 03 May 2017. Web. 03 May 2017. Video

Zusman, Michael C. “What It Really Takes to Make Artisan Chocolate.” Eater. N.p., 11 Feb. 2016. Web. 03 May 2017.

Video,