A history of the luxurious consumption of chocolate

Ever walked into L.A. Burdick and feel overwhelmed with the vast selection of chocolates offered? Once upon a time, there was only one form of consuming chocolate: by drinking a concoction of cocoa and spices. However, through the interactions of different civilisations and cultures, chocolate consumption blossomed to various forms, including the confections seen at L.A. Burdick. L.A. Burdick Chocolate is a New Hampshire-based chocolate company specialized in “handcrafting artisanal chocolate and confections”. L.A. Burdick Chocolate is part of a growing global movement of fine chocolatiers and demand for fine cacao products, with 480+ specialty chocolate makers across six continents (Martin). The products of these specialty chocolate makers typically command higher prices compared to well-known brands (Mars, Hershey’s, Cadbury etc.) sold at a convenience store. The difference in prices stratifies the consumption of chocolate to different socioeconomic classes: the mass-market and the luxurious. An examination of the history of chocolate and the current products offered will reveal why the socioeconomic stratification exists and reveal the possibilities for the future of chocolate consumption.

The earliest known form of chocolate consumption was a beverage of cacao, spices, flowers, and grains found within the Olmec civilization. Written records and archaeological artefacts suggest the drink was found in important occasions such as religious rituals, marriage rituals, and funerals (Coe 34-36). Furthermore, the Mayans and Aztecs believed cacao to possess spiritual and medicinal powers and associated a strong value with cacao beans, culminating to a currency system based on cacao beans as outlined in a Nahuatl document in 1545 (Coe 99). Undoubtedly, the elites would possess more cacao beans than other members of society and have better means to produce the chocolate beverage. These historical records show the luxurious consumption of chocolate is not a modern, but rather an established concept tied to the origins of chocolate.

The beginning of trades between the Americas and Europe introduced cacao and chocolate consumption to the European elites. After learning the indigenous practices for chocolate preparation and consumption, catholic priests brought the knowledge and accompanying ingredients back to Europe and reported their findings to the social elites (Coe 125). The scarcity of the ingredient in Europe (before the slave trade) precluded the masses from learning about or consuming chocolate. Those with the means to consume cacao would host chocolate parties to share the experience with other social elites, effectively labelling chocolate as a luxurious good requiring its own extravagant occasion. An example of this occasion is the reception of Cosimo de’ Medici (a powerful and wealthy family from Italy) by the Spanish royal family in 1668 with a bullfight accompanied with candied fruits and cups of chocolate (Coe 135). Furthermore, the preparation and consumption of chocolate had different nuances across different European countries. From Spain to Italy to France to England, each country infused their culinary culture into chocolate. The Spaniads brought chocolate consumption from the colonies to the bullfights. The Italians added “novel, perfume-laden flavors into chocolate” for an additional layer of aroma and taste. The French developed exquisite silver and gold chocolatiere to serve chocolate. The English opened chocolate houses for men to enjoy the beverage and spread of sedition (Coe 135-167). One theme that is common across all countries is an attachment of social class to the consumption of chocolate – seating areas in bullfights, access and use of perfume, high prices for rare metals, and convening to discuss politics.

However, the consumption of chocolate eventually trickled-down to the masses of European society. In addition to the introduction of chocolate houses, the British also introduced sugar and milk into the recipe for chocolate beverages. The sweetness of sucrose was more palatable than the bitterness of chocolate and quickly gained traction with new consumers (Mintz 108-111). Moreover, the industrial revolution brought innovations which made chocolate preparation and consumption faster and more accessible. The hydraulic press invented in 1828 separated cocoa liquor into cocoa powder and butter, enabling a faster preparation of chocolate drinks. Fry’s production of the first chocolate bar in 1847 meant chocolate could be easily transported and consumed anywhere and anytime. Peter in 1879 incorporated milk into chocolate bars and the milder and sweeter taste was widely received till this day. Even after the spread of chocolate to the “masses” in Europe through industrialization, chocolate was not enjoyed by lower-class citizens (laborers and slaves) in imperial colonies, who were responsible for growing the very ingredients in chocolate (Coe 264). Therefore, chocolate consumption remains a luxurious consumption in many parts of the world, despite a change and a trickle-down of chocolate consumption from beverages amongst the social elites to confectionaries for citizens in developing and developed countries.

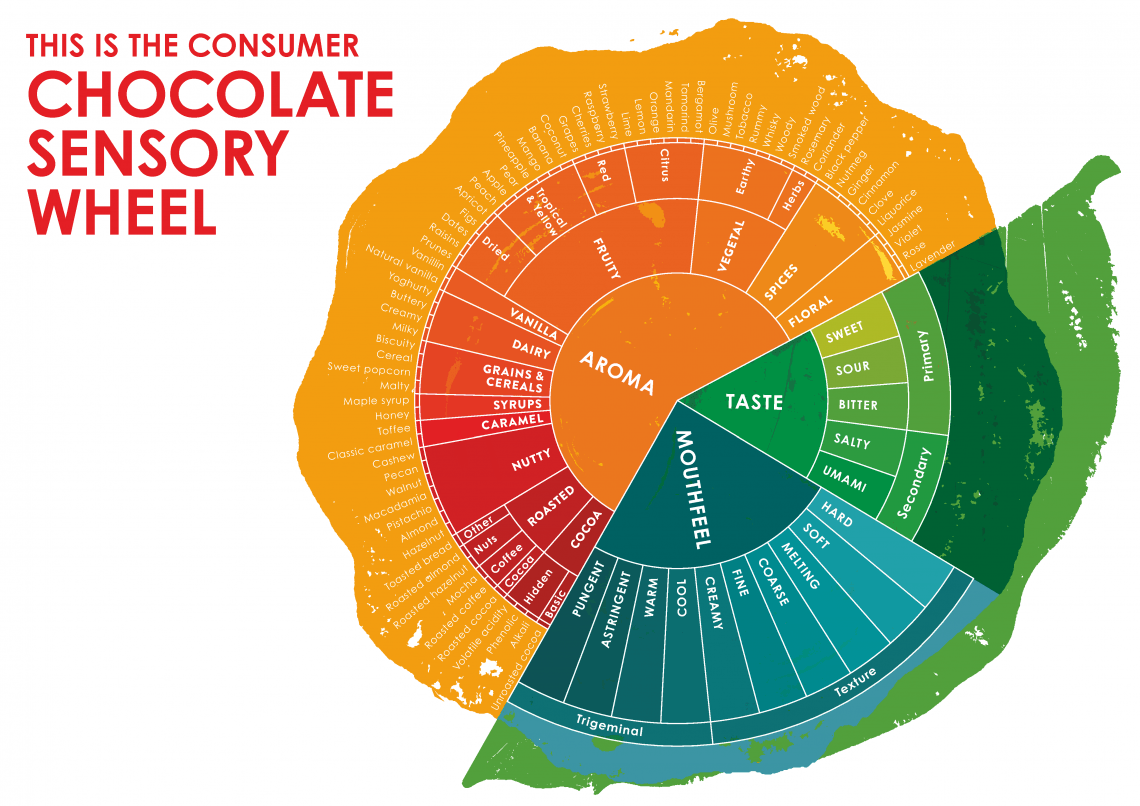

Economic and industry-specific developments after the industrial revolution ensured an uniform taste and quality in chocolate, which in turn created a market opportunity for “fine” chocolate and chocolatiers. With the aid of machines and refinement of chocolate recipes, many chocolate makers improved and standardized the chocolate-making process. A classic example is the rise of Hershey as one of the largest confectionery producers. Hershey arrived at a different formula for producing milk chocolate bars than the Europeans, but an early entrance to the American market won the preferences of consumers. To cope with the large demand for the chocolate (reaching $2 million in sales in 1910, only 7 years after the founding of the company), Hershey built a town surrounding the factory for workers to live in – effectively regulating their work hours and life outside the factory doors (D’Antonio). Hershey even attempted to control the sugar and milk supply chain to minimize disruptions to the production line and regulate the taste of the final product. Also around the same time, other industrialization developments were made in the food industry as highlighted by Goody. Developments in transporting goods with railways allowed chocolatiers to share their products across the US. Developments in preservation techniques influenced chocolatiers to add other elements into the products to increase the product shelf life. Developments in retailing and wholesaling changed the format of chocolate sales to stores and a larger emphasis on packaging to attract customers (Goody). These changes meant large chocolatier companies like Hershey’s, Mars, and Cadbury reached a larger network of customers but also reduced the wide variety of tastes in chocolate in favor of an uniform, widely-accepted taste. As an example, a quick look at the product offering on Hershey’s website implies no variety in the chocolate products (except between milk and dark chocolate), but a variety in the confectioneries that contain chocolate and other ingredients (peanuts, almonds, mint, caramel among others). The homogeneous treatment of chocolate by the big chocolate companies left discerning chocolate-eaters and those seeking something different, hereby referred to as “elites”, searching elsewhere for a wider variety of taste profiles in chocolate.

To cater to these “elites” and differentiate themselves from the large corporations, smaller chocolatiers developed “fine” chocolate and confectioneries demanding a market premium for the extra effort in the production process. In the late 20th century, the large corporations placed significant market pressure on French chocolatiers with the introduction of chocolate at a lower price point. Then, the invasion of foreign franchise outlets in the French confectionery market enabled people with little know-how about chocolate to sell mass-produced products with a successful marketing campaign (Terrio 35-36). Local French chocolatiers had to rebrand themselves as a professional practice, re-educate consumers to discern between different chocolate, and persuade the government to acknowledge the work as undeniably French. The culmination of these efforts are competitions and trade shows such as the Meilleur Ouvrier de France and Salon du Chocolat. These competitions and trade shows elevates chocolate to the equivalent level of high-end artwork and fashion. The change brought by French chocolatiers was successful in raising the standards and awareness of consumers, but also attracted the attention of the large corporations and some efforts are now backed by the corporations (such as Linxe’s La Maison du Chocolat bought out by Valrhona, a subsidiary of Savencia Fromage & Diary, and corporate sponsors of Salon du Chocolat). Nonetheless, the French chocolatiers carved out a chocolate market segment which appreciates chocolate as a form of art and willing to pay the premium for such consumption.

The growth of the fine chocolate industry in Europe quickly drew the attention of chocolatiers across the globe. Artisan and craft chocolate grew in two directions: artisanal confectioneries and flavor-centric chocolate. L.A. Burdick is an example of the growth in artisanal confectioneries. Larry Burdick learned chocolate-making in Switzerland before returning to New York to establish the company (Burdick). Although Burdick specifies the source of the cacao beans from Grenada, the product offerings are truffles and ganaches of varying flavors with a couverture (chocolate with extra cocoa butter). The presentation and packaging of artisanal confectioneries and the variety of flavors ensure the products can be great gifts for a wide audience. The practice of gifting artisanal chocolate is especially common in East Asian culture, where the gift transmits certain connotations from the bearer to the receiver. Hence, the popularity of artisanal chocolate is far greater than the popularity of bean-to-bar chocolate in Japan and China. On the other hand, there are flavor-centric chocolate makers such as Dandelion Chocolate. As outlined in their website, Dandelion Chocolate is focused on bringing out the flavor profiles of cacao beans and the fermenting and roasting process. This also means the products offered only consist of two ingredients: cacao and sugar. As products are handmade in small batches, different flavor profiles can be accentuated from the same chocolate across different batches (Dandelion). This gives the consumer an unique experience of the chocolate and the often-limited products increase the desirability and price per chocolate bar. Another argument for the bean-to-bar movement is the benefits brought to cacao bean farmers. The beans are usually sourced directly from the farmers to the chocolate makers, and often with an exchange of knowledge between the partners. However, despite the 230+ bean-to-bar craft chocolate makers, the number of cacao farmers in direct partnerships with chocolate makers remains small relative to large corporations and the current state of the supply chain and industry overall remain problematic. Moreover, the sheer size of the large, industrial chocolate makers create a market imbalance and leave craft chocolatiers vulnerable to buyouts of their cacao bean supply. Overall, the consumption of high-end chocolate has now diversified to two main streams of artisanal confectioneries and flavor-centric chocoolate, and both segments are small and remain threatened by the large corporate chocolate makers.

Artisan and craft chocolate grew in two directions: artisanal confectioneries and flavor-centric chocolate.

L.A. Burdick Chocolates, with a focus on the flavors and presentation of confectioneries. (Source)

Dandelion Chocolate, with a focus on the flavor of the cacao from different sources. (Source)

After tracking the history of luxurious consumption of chocolate, one may wonder what the future trend of high-end consumption of chocolate will be. As always, predicting the future is near-impossible but chocolate may have the potential to be elevated to the level of wine as a luxury good. Many parallels have been drawn between chocolate and wine. Both food types rely heavily on a single crop with dozens of varieties. Both are labor-intensive in the production process. Both can have very different taste profiles in the end product. Yet, wine can command far greater prices than chocolate. To bridge this price gap and elevate chocolate to a luxury good, three things must happen first: shift the marketing strategy of chocolate, reduction of power imbalances in the supply chain, and gain greater recognition on all levels of society. First, current marketing of chocolate presents chocolate as a symbol of happiness or joyful bliss. Yet, chocolate provides a more rounded experience than an emotion – there are hundreds of compounds delivering a complex taste profile – and chocolate would not be a luxury good on the level of wine unless the general consumer learns, through marketing, to appreciate the depth of taste. Second, wine is usually produced in the vicinity of the vineyard. This means those who produce the grapes are also the ones who process the grapes into wine. This allows the wine producer to accumulate and use knowledge about the grapes to produce better wine. In contrast, the chocolate industry has a large rift between the cacao farmers and chocolate makers. The disconnect between the two parties means there is little shared knowledge and the best cacao beans may not be processed correctly or vice versa. The bar-to-bean movement is a good step forward in mending the rift within the chocolate industry. Third, wine is celebrated as a produce by national and local governments such as France, Spain, Argentina, and California. This promotion then garners a global reputation for the wine and recognition of the vineyards. However, for chocolate, the cacao’s origin is usually unspecified and, even if specified, at most reaches the region and type of chocolate. The lack of recognition, especially in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, does not support or protect the farmers for producing quality cacao. The three roadblocks listed above are in no way simple or easy to resolve, but with people and institutions across the industry attempting to change the situation, one can hope chocolate will be elevated to a luxury good in the near future. Who knows, maybe one day there will be chocolate sommeliers and people can enjoy chocolate pairings with a 12-course meal at a Michelin 3-star restaurant.

Works Cited

Burdick, Larry. “L.A. Burdick Chocolates -.” L.A. Burdick Handmade Chocolate, 2019, www.burdickchocolate.com/.

Coe, Sophie D. The True History of Chocolate. 3rd ed., Thames & Hudson, 2013.

Dandelion Chocolate. “How We Make Chocolate.” Dandelion Chocolate, 2019, www.dandelionchocolate.com/process/.

D'Antonio, Michael. Hershey : Milton S. Hershey's Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams. Simon & Schuster, 2006.

Goody, Jack. “Industrial Food: towards the Development of a World Cuisine.” Cooking, Cuisine and Class, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1982, pp. 154–174.

Martin, Carla D. Sizing the Craft Chocolate Market. Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute, 31 Aug. 2017, chocolateinstitute.org/blog/sizing-the-craft-chocolate-market/.

Mintz, Sidney W. Sweetness and Power : the Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin Books, 1986.

Terrio, Susan J. Crafting the Culture and History of French Chocolate. University of California Press, 2000.

You must be logged in to post a comment.