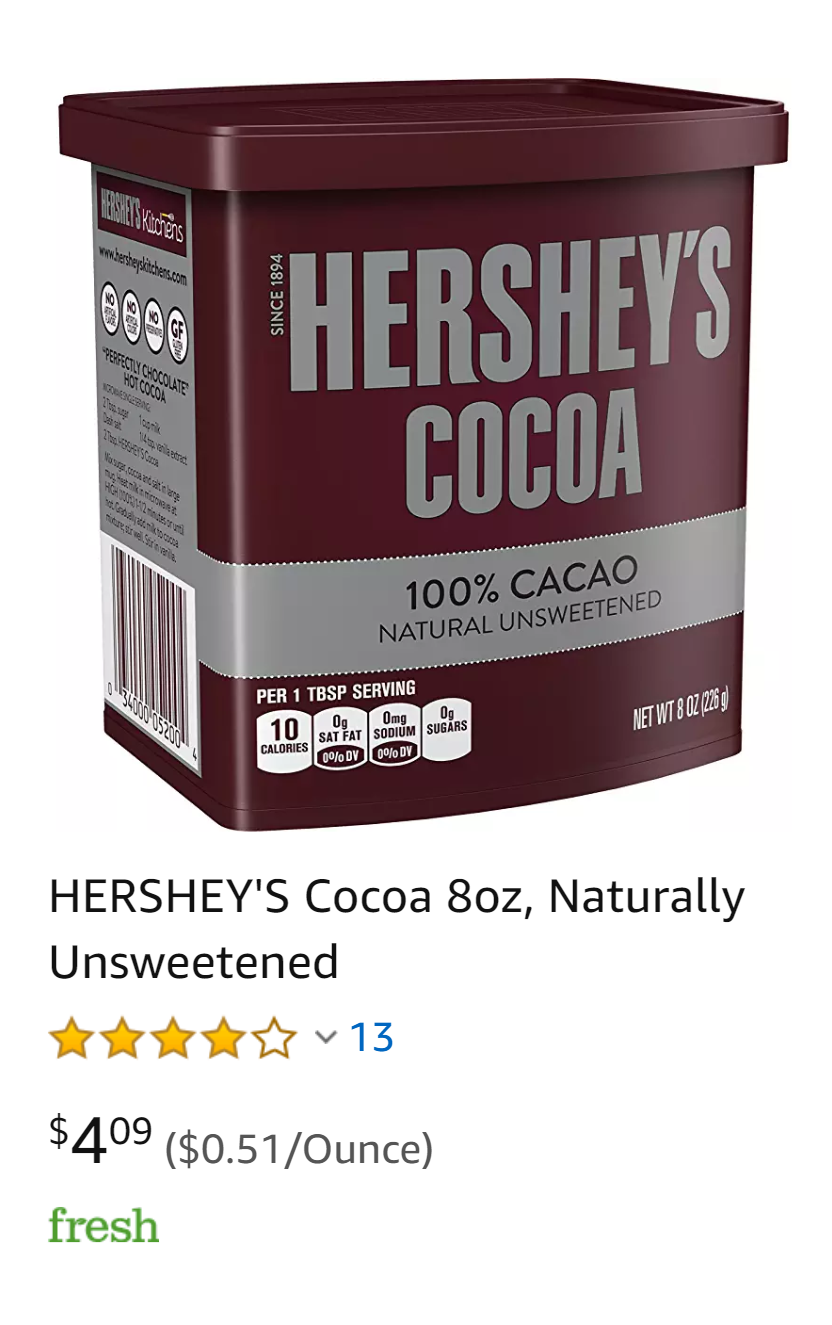

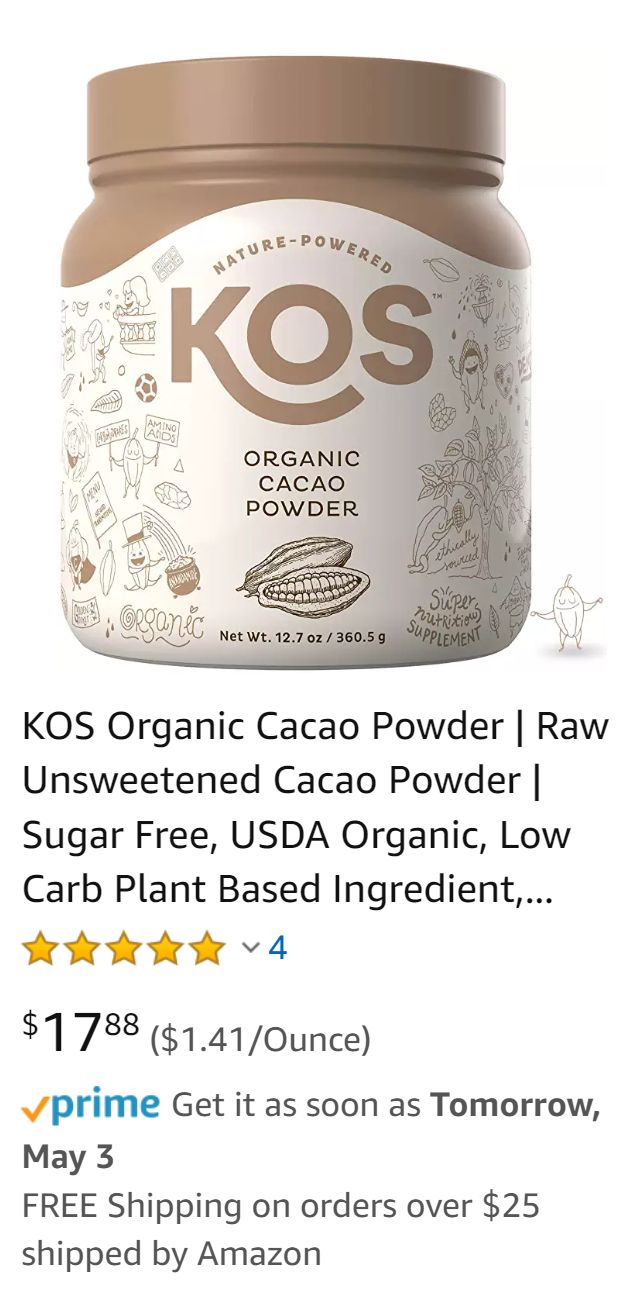

The ubiquity of cheap chocolate is no longer enough to capture the gaze of today’s consumer. We are now being lured away from Hershey kisses and Snickers candy bars towards a more exotic temptations—things like raw cacao powder. In fact, as represented by the two products below, the market is willing to pay almost three times more.”[1] We want to pay more for less product, and this phenomenon doesn’t just stop at cocoa powder. Something is pushing the door wider for cacao nibs, bean-to-bar craft chocolate, and artisan confections to emerge. I argue that chocolate is once again diversifying to a new state of nonsensical luxury, relying on contradictions within the organics movement, slow food movement, and the idea of decadence itself.

This familiar Hershey’s 100% Natural Unsweetened Cacao is worth 1/3rd the price of this organic raw cacao powder above. Both are from Amazon.com.

Historical Background

For most of its history, chocolate has for the elites. The Olmecs (1500-400 B.C.) are attributed with the first domestication of Theobroma cacao. This is supported by research reconstructing their ancient word kakawa for what we today call “cacao.”[1] While little is still known about this people, we know that they passed on “the plant, the process, and the word kakawa” to the Maya. For the Maya, this food had high significance in important cultural narratives, burial rituals of the upper-class, and associations with the gods. While we are unsure if the lower class could consume it, the Mayan elite certainly did at ornate feasts. Cacao was also highly held by the Aztecs, who used it for religious rituals, nutrition during travel, and currency. For these reasons, their royalty and aristocrats ate cacao in the form of frothy drinks as a show of power.

During the conquest of the Aztecs in the early 16th century, conquistadors, missionaries, and merchants sent cacao beans and chocolate drink recipes back to the royalty in Europe.[1] As Coe and Coe describes, “At first, the only people in Europe who drank cocoa were Spanish royalty and their courts. Thanks to intermarriages between royal families and the circulation of fashionable trends among them, a taste for the drinks spread, first to southern Europe, then northward.” [2]To clarify, this spread across Europe was still confined to the royalty in those respective countries. By the 1600s, it trickled down to British aristocracy and intelligentsia, who talked politics in chocolate and coffee houses. It was only by the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s that cacao became truly democratized and accessible to everyone.[3] This was caused by technological advancement and product development, leading to the rise of chocolate company giants. In sum, this food has only been a household product for a short 200 years.

The Organics Movement

However, recent diversification of products for multiple audiences has caused us to reinforce the association between cacao and class that had been relaxed by the Industrial Revolution. One clear example is the company barkTHINS, founded in 2013. Taking on the mid to upper-middle class market, barkTHINS are explicitly sold as a “snacking chocolate.” The back of a package of their dark chocolate, almond, and sea salt bark reads: “barkTHINS are snackable slivers of dark chocolate paired with real, simple ingredients for a completely original take on snacking. Fair Trade Ingredient Certified and Non-GMO Project Verified, barkTHINS are a mindful and sophisticated way to snack. It’s Snacking. Elevated.” This also introduces how organic food and higher price-points together have facilitated an intangible link between non-GMO food and luxury.

In her article “Fast Food/Organic Food: Reflexive Tastes and the Making of ‘Yuppie Chow,’” Guthman uses the case study of organic salad mix in California to look at the greater social movement. The original motivations for organic farming were the “public health, environmental and moral risks involved with chemical-based crop production and intensified livestock management.”[1] San Francisco was a particularly conducive environment of post-counter culture combined, haute cuisine culture, and people with expendable income. When Alice Waters spearheaded the idea of cooking with local ingredients, she marketed and sold organic salad mix in what was soon to become an upscale dining establishment. The ties between organic and the upper class became a trend as more elite restaurants copied the idea of selling organic salad mix. However, as this caught on, the dynamics began to change. Restaurants were willing to pay more for greens that were fresher and aesthetically pleasing.[2] In return, growers could make more money with a small batch yield. Eventually, this incentivized the scaling-up and streamlining of processes to produce a greater bounty of beautiful vegetables. The growth and adoption of the organic food into mainstream culture ultimately moved it further away from its core ideals.

Just

like salad mixes, non-GMO and virgin/raw chocolate are examples of cacao

products emerging as luxury goods. However, it has also inherited the pitfalls

of the overall organics movement. To reiterate, the point is to eat food as

natural as possible. In the video above, we can see that process. However, it

is important to note his low yield at he end. To ensure supply for the

increasing demand of virgin chocolate, companies will inevitably need to turn

to extensive industrialization. Moreover, virgin cacao is advertised to boost

mood, clean out toxins by increasing blood flow, and aid better digestion.[1]

The fresher seems to be the better! However, the video shows how natural

processes might enable unregulated bacterial growth. Working bare-handed, it

seems that raw chocolate would be more dangerous than regular chocolate because

of the bacteria on the shell covering the nib. To keep it food-safe, raw

chocolate likely requires stringent processing if sold mass-scale.

The Slow Food Movement

Related, but distinct from the organics movement, analyzing the push for slow food will help us more deeply analyze the issue of food safety introduced in the section above. Rachel Laudan remarks that Culinary Luddism runs rampant, such that we scorn all industrialized food. It is a trend to yearn for food that is somehow more real, fresh, and natural for the health benefits. However, one shouldn’t wish for food that grandma had growing up. Laudan clarifies that “natural was something quite nasty. Natural often tasted bad. Fresh meat was rank and tough, fresh milk warm and unmistakably a bodily excretion: fresh fruits (dates and grapes being rare exceptions outside the tropics) were inediblely sour, fresh vegetables bitter..” [1] In addition to this, food would often quickly go bad and be difficult to digest. Advancements in regulated industrialization allows our food to be flash-frozen or our milk pasteurized before bacteria colonies grow. In these respects, fast foods have allowed safe food to be more accessible. Yet, it is a fair point that such foods are not always nutritionally balanced.

Because the

organics and slow food movements are so intertwined, by looking at both we

better understand how the popularity of raw chocolate for its alleged health

benefits might be premature. Industrialized food protects against many food-safety

issues. Slow food introduces risk. This is the case for raw milk, raw water,

and raw cacao. Finally, from the salad

mix case study, we know that freshness has been associated with the elite.

However, Laudan states, “Eating fresh, natural food was regarded with suspicion

verging on horror, something to which only the uncivilized, the poor, and the

starving resorted.”[1]

This indicates a reversal of what luxury has meant over time.

Redefining Luxury as Immaterial

In the video above produced by

the Bon Appetite Test Kitchen,[1]

pastry chef Claire Saffitz is tasked with the goal of making gourmet Ferrero Rocher

chocolates. As part of a series where she had previously recreated Kit Kats and

Snickers, this one particularly stands out; Saffitz remarks this candy is

already considered fancy. She says, “Yeah, I think hazelnut is like a

sophisticated flavor. Whether or not its actually fancy, it’s marketed to be

thought of as a fancy treat.”[2]

So, how does she make it even more luxurious? She decides, “I just want to use

really nice chocolate, toast some hazelnuts. And then I think overall, the

improvement will just be in those details.”[3]

These seemingly banal points bear great significance that can be next understood

with McNeil and Riello’s work Luxury: A

Rich History.

The attempt to make something currently sold as a luxury more gourmet indicates a hierarchy in what we define as high goods. When we imagine what luxury must have meant to past kings and queens, we would have said consumption and accumulation of fine things. What matters is exclusivity and scope, and consumption would have certainly stood out in a world where some people were struggling to survive from famine. However, the video below spotlights a nuance.

This video portrays a more extreme kind

of luxury closer to extravagance. It showcases chocolate created to look like a

gold ingot, called the Louis XIII Grand Gold Bar. It alludes to a French king

with namesake cognac caramel filling and liberal spraying of 23-karat edible gold.

With an elaborate, custom-made box for a single chocolate eaten at the

restaurant, the key quality here is that it is “so over the top.”[1]

McNeil and Riello terms this uber luxury. They state the “top end of the luxury

market now needs to be extravagant (or elitist) beyond belief, because basic

luxury is within the reach of too many today.”[2]

This fits well with a point Saffitz made. She joked, “If you’re, like, trying

to buy a gift for someone at the [laughs] drug store, this is your best option

to look fancy.”[3]

This suggests that finding the chocolate at the drug store runs counter to the

idea of uber luxury because of Ferrero Roche’s ubiquity. However, it remains to

be what McNeil and Riello would call life’s smaller luxuries. In chocolate,

this might be what craft chocolate bars are, priced at about $5-6 compared to a

Hershey’s bar.

Additionally,both videos indicate luxury has moved from a consumption of things to a consumption of another’s labor. McNiel and Riello write: “In this new vision of luxury, more than simple money is required from its consumer. Time and knowledge are key concepts in the very notion of twenty-first century luxury…‘distinction,’ the need to appear different from others, was not just achieved through the purchase and use of luxurious and expensive objects. It was also performed through the conspicuous expenditure of time in what we might call useless activities.”[1] In Saffitz’s case, if the ingredients stayed more or less the same, the thing that made her chocolates gourmet was that it was handmade. To recreate them took an abundance of her time and her knowledge from culinary school. Another, similar example would be the chocolate art below. Therefore, a person who eats them does not waste time doing a useless activity. Rather, they are imbibing the time spent by another person, who could have spent it doing something else. Therefore, artisan or gourmet chocolate is built on an incoherence embedded within the definition of high luxury. The good does not have to contribute to creating tangible improvements to one’s life. Productivity does not matter, and it is the irrationality that makes it valuable. It cannot be understood by outside people. Insiders would consider the good as extraordinary, and outsiders would think it wasteful. The separation between classes is what is underscored.

Conclusion

In sum, chocolate is moving in a direction of decadence with multiple levels of contradiction embedded within it. It benefits from the organics movement, but moves further and further away from the idea of non-industrialized food. The idea of craft and gourmet chocolate parallels the slow food movement, but disregards the values of food safety previously held by the old upper class. At least in part, modern elitism in food is changing from material consumption to the consumption of experience and time. An implication of these trends is that chocolate is re-positioning itself as a crossroads of class. High-end chocolate is considered more delicious and healthier, as a higher price point pays for its quality and non-GMO status. Philanthropy also tends to be incorporated, like how people will agree to pay more for the humanitarianism of the Fair Trade Certification. But, not everyone can afford to be charitable. In contrast, the chocolate affordable by the people financially unstable is framed as lower-end food. It is less expensive, but more meaning than that is being infused into the idea of “cheap.” By “cheap,” we are insinuating accessible chocolate is not delicious and not “real” chocolate. The dimensions of taste, health attitudes, and philanthropy contribute to how cacao is becoming increasingly more socially charged.

Bibliography

Multimedia

“Amazon.Com: Hershey’s Chocolate Powder.” Accessed May 3, 2019. https://www.amazon.com/s?k=hershey%27s+chocolate+powder&ref=nb_sb_noss_2.

“Amazon.Com: KOS Organic Cacao Powder | Raw Unsweetened Cacao Powder.” Accessed May 3, 2019. https://www.amazon.com/s?k=KOS+Organic+Cacao+Powder+%7C+Raw+Unsweetened+Cacao+Powder&ref=nb_sb_noss.

Bon Appétit. “Pastry Chef Attempts to Make Gourmet Ferrero Rocher.” YouTube, February 12, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XY-hOqcPGCY&t=38s.

“We Tried A Boozy Golden Chocolate Bar – YouTube.” Accessed May 3, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05jOGEmriqo.

Lane, Jim. “Art Now and Then: Chocolate Art.” Art Now and Then (blog), February 29, 2016. http://art-now-and-then.blogspot.com/2016/02/chocolate-art.html.

Other Sources

Coe, Sophie D., and Michael D. Coe. The True History of Chocolate. 3rd edition. London: Thames & Hudson, 2013.

Guthman, Julie. “Fast Food/Organic Food: Reflexive Tastes and the Making of ‘Yuppie Chow.’” In Food and Culture: A Reader, edited by Carole Counihan and Penny van Esterik, 496–509. New York and London: Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group, 2012.

Laudan, Rachel. “A Plea for Culinar Modernism: Why We Should Love New, Fast, Processed Food.” Gastronomica 1, no. Feb 2001 (February 2001).

Leissle, Kristy. Cocoa. Newark, UNITED KINGDOM: Polity Press, 2018. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/harvard-ebooks/detail.action?docID=5294996.

McNeil, Peter, and Giorgio Riello. Luxury: A Rich History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Citations

[1] McNeil and Riello, Luxury, 239.

[1] “We Tried A Boozy Golden Chocolate Bar – YouTube,” pt. 0:44.

[2] McNeil and Riello, Luxury, 231.

[3] Bon Appétit, “Pastry Chef Attempts to Make Gourmet Ferrero Rocher,” pt. 1:05.

[1] Bon Appétit, “Pastry Chef Attempts to Make Gourmet Ferrero Rocher.”

[2] Bon Appétit, pt. 0:55.

[3] Bon Appétit, pt. 4:09.

[1] Laudan, 38.

[1] Laudan, “A Plea for Culinar Modernism: Why We Should Love New, Fast, Processed Food,” 36.

[1] “Amazon.Com: KOS Organic Cacao Powder | Raw Unsweetened Cacao Powder.”

[1] Guthman, “Fast Food/Organic Food: Reflexive Tastes and the Making of ‘Yuppie Chow,’” 497.

[2] Guthman, “Fast Food/Organic Food: Reflexive Tastes and the Making of ‘Yuppie Chow,’” 499-500.

[1] Leissle, Cocoa, 38.

[2] Leissle, 38.

[3] Leissle, 38–39.

[1] Coe and Coe, The True History of Chocolate, 35.

[1] “Amazon.Com: KOS Organic Cacao Powder | Raw Unsweetened Cacao Powder.”